The remarkable story of Harry Edward: Britain’s first black Olympian

Harry Edward, who took 100m bronze at the 1920 Antwerp Games, enjoyed an extraordinary running career but he deserves to be far better remembered

Harry Edward took a deep breath, pushed his spikes into the holes he’d just dug in the sodden cinder track and dropped his head.

A vos marques.

It was the biggest race of his life. The 100 metres final at the 1920 Olympic Games, in Antwerp.

Preparez vous.

As he waited for the gun to blast, a Belgian official shouted at the American champion Charley Paddock to pull his hands back behind the line. The instruction broke Edward’s focus and concentration and he relaxed a little, expecting a delay or even a call to stand up.

Partez.

Instead, the pistol fired and he was left trailing as the small crowd roared and the world’s fastest men disappeared in front of him. With his fluid, eight-foot stride, he managed to catch almost all of them as he blasted down the outside lane, but as the six men hit the tape it was Paddock first, his fellow American Morris Kirksey second and, incredibly, the fast-finishing Edward was judged to have pipped Jackson Scholz on the line for third.

In those early Olympic years a British bronze medal was greeted amiably enough – he even got another in the 200 metres – but his exploits did not trouble the front pages. In truth they hardly troubled the sports pages. It was, however, a genuinely significant moment.

As he climbed down from the podium after receiving his medal, a watching black American athlete ambled shyly across the in-field to talk to him. “Do you know that you are the first man of colour to stand on the platform of Olympic winners?” he explained.

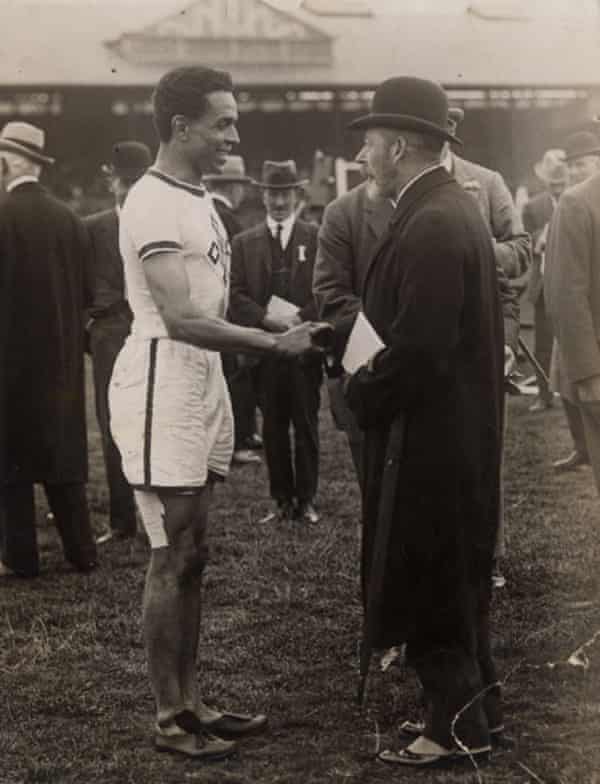

Harry Edward was indeed Britain’s first black Olympian, also its first black Olympic medal winner, and he enjoyed an extraordinary running career – once winning the 100-, 220- and 440-yard titles at the AAA championships inside a single hour – and being personally congratulated by King George V.

Thanks to the Amistad Center, a research and museum facility in New Orleans devoted to the United States’s racial and ethnic history, Edward’s remarkable life can be remembered in all its glory. His papers, photographs and memorabilia, including an unpublished memoir, have been sitting there gathering dust for nearly 50 years.

The 257-page typewritten memoir – entitled “When I Passed the Statue of Liberty I Became Black” and sub-titled “The Autobiography of an Ex-European” – is no standard sporting opus. It is an eye-opening piece of work that traces his globe-trotting adventures as a kind-hearted, self-effacing, smart, liberal-minded evangelist for human rights, a man way ahead of his time, as he moved through some of the 20th century’s most seismic events – from the misery of a Great War internment camp, through the Depression and the struggle for civil rights in America, to the internecine politics of Vietnam. The last paragraph of his memoir reads: “I hope that the story of my economic struggles in the face of racial obstacles may provide similar encouragement and inspiration and contribute in some constructive ways to urgently needed reforms and changes.”

Edward was born in Berlin, in 1898, to a Prussian piano teacher and a father who became a cabin boy to escape grinding poverty in the British colony of Dominica, and, arriving in Europe, worked as a circus entertainer and a popular maitre d’ at some of the German capital’s top restaurants.

By his teens Edward could speak fluent German, French and English and was showing both academic and athletic promise. His speed was first noticed at a track meet in Berlin, at the city’s new stadium built to stage 1916 Olympics, where, at only 16, he placed second in the 100m to the German champion and won the 200m. It was 28 June 1914. A few hours earlier Archduke Franz Ferdinand had been shot dead in Sarajevo, an event that foreshadowed a chilling chain reaction among European governments.

The war would change his life. As a British subject resident in Germany, the secret police soon came calling and after six months of forced curfew he was arrested and, completely alone, whisked off to Spandau, on the outskirts of Berlin, where he was interned in the grim POW camp at Ruhleben – literal translation “Life of Rest”.

Edward’s account of his time in the camp, almost four years of it, is depressing and entertaining in equal measure. He won the camp sports day races, joined the dramatic society, made lasting friendships, while also witnessing daily torture, brutality and death. He existed on meagre rations, augmented by wood shavings, and slept in a freezing old stable block. “The quality of the food grew progressively worse; black bread was adulterated with sawdust, potato peelings and powdered bones. Horsemeat of animals killed at the front was pickled in brine and sent to prison camps. Turnips were served as the only vegetable every day for four to five weeks.”

Ruhleben was among the first camps to be liberated at the end of the war and in the winter of 1918 he found himself in London, where he learned he had passed the exams he had taken in the camp and secured a job as a teacher of German and French. “In this post-war period it was sports again which provided me with an opportunity to emerge as an individual and to express my philosophy.” In his first track meet in Britain, at Stamford Bridge, he won two prizes. He swept the sprint events at the 1920 AAAs and was selected for the 100m, 200m and sprint relay team at the Antwerp Games, alongside a young Abrahams. Harry battled his way through to the final of the 100m before falling victim to the calamitously bungled start.

“I put tremendous effort into my strides, found myself about four feet behind the leaders at half distance, regained an improved forward-leaning position and ended with a tremendous burst, passing everybody at the end. Alas, I passed them about three feet behind the finishing line. The judges gave me third place. There was a great delay before the results were announced. Every participant sensed or knew that the start had been a doubtful one. Scholz, a US finalist, said to me at the end of the race that it had been a false start. He had been left on his knee at the start.”

The following year Edward defended his sprint titles at the AAAs, but it was 1922 that would go down as the zenith of his athletic career, with Edward winning countless titles, handicaps and invitationals – though in those strict amateur days the biggest prize he could earn was seven guineas – culminating with the AAAs where, inside one hour, he placed first in the 100-, 220- and 440-yard finals, a record that has never been beaten.

In 1923, inspired by an invitation to run at New York’s Yankee Stadium, he emigrated to the US. “Upon my setting foot on the soil of the United States of America I learned very soon that among all the classifications given me, the designation ‘Negro’ was the most significant,” he wrote later. Edward’s performances on the US tracks were disappointing and he continued his extraordinary life story away from the track, odd-jobbing around New York, then moving to Philadelphia. In the 1930s he returned to New York, divorced and remarried, and became the administrative director of the Negro Theatre, working with the likes of John Houseman and Orson Welles, and staging the first version of Macbeth with a black cast. He spent the second world war heading an uptown rationing operation for the Office of Price Administration, and when hostilities came to an end, he volunteered to join the newly formed UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. They sent him to Greece.

En route and accompanied on a bumpy seaplane ride by a collection of snooty British civil servants, he returned to London for the first time and wondered how he would be treated. “After disembarkation at Poole all passengers had to pass through British security. The supervising officer of that service looked at my American passport then bestowed a long look upon me ending in the query: ‘Ain’t you Harry Edward of the Poly Harriers, the former British champion?’”

After the war he returned to the US and took another grey clerical job, this time at the New York Employment Office, a role he continued until retirement in the late 60s. But he continued to work abroad and travelled to Vietnam to set up a US sponsored foster-kids programme and worked at the UN and the New York mayor’s office, greeting foreign dignitaries.

Edward ought to be revered as a legend of British sport, mentioned in the same breath as Abrahams and Eric Liddell. But he isn’t. When he died, after a heart attack on a trip to visit his sister Irene in Germany in 1973, the New York Times printed a five-paragraph obituary, while the black New York Amsterdam News printed a larger article, alongside a picture of Edward with King George V back in 1922. Not a single line was printed in the British press.

It was scant recognition for a true sporting pioneer and a man who lived his life on the coalface of so much 20th century political change, but proof positive, were it needed, that his racing career and the wonderful, eclectic life that followed, had been essentially air brushed from history. Today, nearly 50 years after his death, and in the heat of the Black Lives Matter campaign, he would surely be crestfallen to learn that the struggles he endured daily have not materially changed?

His fascinating autobiography demands to be published and wheels are in motion to get it done in time to mark the centenary of his marvellous AAAs exploits in 1922. Despite its vintage, Edward’s story remains as valuable, instructive, and sobering as it did when he wrote it more than 50 years ago.

1 comment:

A brilliant bit of sleuthing and a riveting read! Great work guys and thanks again for all of your efforts

Post a Comment