It has been a few weeks since last posting, and I have a couple of good stories to relate, but we are rapidly approaching Nov. 11, 2018, the hundredth anniversary since the Armistice in Europe ending WWI. I've had a hero in mind to honor, not of that war but WWII. We've posted stories in the past of men and women who were Olympians and who died fighting for their countries in both good and by some historians' definitions in bad causes. Nevertheless those angels and scoundrels suffered the same fate answering their countries' demands on them and paying with their lives. We honor those men and women this week and all weeks.

Olympians Who Died in War Here is the link to that earlier post.

The man I wish to remember this year is different in that he did not die in combat. Instead he led his troops to a victory. That victory was Iwo Jima in the Pacific. His battalion raised the flag on Mt. Suribachi. He was not in command of the whole Iwo Jima operation, but he was on the ground leading his unit, the 28th Marines. Not the safest place to be that month.

|

| Harry Liversedge |

I'm talking about Harry Liversedge. Hardly a household word these days yet one who over the years proved himself tough as the proverbial keg of nails. I've not found a picture of Harry Liversedge smiling. He must have been a serious man going about serious business all his life.

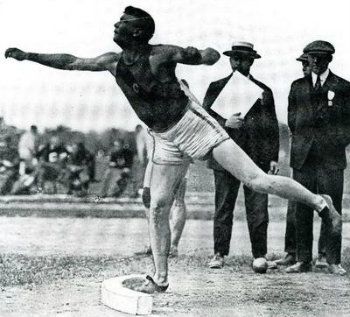

Born in Volcano, California, 70 miles east of Sacramento, in 1894. Harry played football at Cal Berkeley, won the IC4A shot put in 1917, and joined the Marines that same year. He participated in the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp placing third behind two Finns. This was the first time Americans did not win the shot. He got the shot out to about 46 feet, but from these pictures it is clear that he was not a behemoth as many of his contemporaries. Liversedge also qualified for the 1924 games in Paris but did not participate. He died in 1951 and is buried near his birthplace in Pine Grove, CA.

Of note: Liversedge may have played rugby against Eric Liddell when both were based in Tientsien, China in the 1920s, but it is not yet documented. Here is a link to that part of Harry's history.

Liversedge, Rugby, China Clik Here

Here follows a more detailed resume of Liversedge's career both athletic and military.

George

While attending the University of California at Berkeley Harry "The Horse" Liversedge won the shot put at the 1916 IC4A championships. His athletic career was interrupted when he joined the Marines in May, 1917 and this led to him becoming a career Marine Corpsman. He is best known as the General who led the Marine regiment that raised the flag on Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima.

In 1920, Liversedge finished third in the shot at the Antwerp Olympics and with two Finns taking the leading places this was the first time that an American did not win the event. In 1924 he was nominated as an alternate for the shot put but did not start.

Liversedge resumed his Marine career after the Olympics and achieved the rank of Brigadier General. In January 1942, Lt. Col. Liversedge was placed in command of the Second Battalion, Eighth Marines, and was promoted to colonel in May of that same year. From 5 July-29 August 1943, he led this Battalion as it landed on New Georgia Island in the Solomon Islands. For his efforts, Liversedge was awarded the Navy Cross.

In January 1944, he was transferred to the 5th Marine Division and assumed command of the 28th Marines, leading them ashore in the Iwo Jima campaign, for which he was awarded a Gold Star in lieu of his Second Navy Cross. (from Sports Reference)

Harry Liversedge: Cal's Most Heroic Olympian

Harry Liversedge putting the shot for Cal at the Pacific Coast Conference championship meet in 1916.

Note, this is one in a series about early Cal Olympians. Previous stories have been about Cal's first Olympian, Robert Edgren, and Cal's first Olympic swimmer, Ludy Langer.

Harry Bluett Liversedge was born on September 21, 1894 in the tiny gold mining town of Volcano, California, in Amador County. He enrolled at the University of California in 1914. This was in the era when Cal played rugby instead of football, and Liversedge immediately joined the rugby team. As a freshman, he was a starter on the 1914 rugby team, and played in the last rugby Big Game against Stanford. The following year Cal switched back to football, and Liversedge made the transition to the American game, playing on the offensive and defensive lines. The rugby players had a lot to learn about football, but Liversedge and his teammates were fortunate that beginning in 1916, they had the opportunity to learn from one of the best ever -- Cal's new head coach Andy Smith. (For more on the life and career of Andy Smith, click here.)

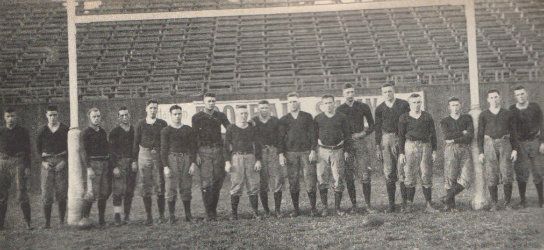

The 1915 Golden Bear football team standing under the goal post at old California Field on the Berkeley campus. Harry Liversedge is the tall player standing seventh from the left.

But it was in track that Harry Liversedge made his biggest mark. He was a standout in shot put, discus, and javelin. In 1916, he helped lead the Bears to the Pacific Coast Conference track and field championship. Cal beat out second-place Stanford 36 points to 31 points, with none of the other eight schools garnering more than 18 points. Cal's track athletes struggled, scoring only 7 points, but Liversedge and the other field athletes saved the day by racking up 29 points. Harry Liversedge finished second in shot put, and won the javelin event, with a throw that established a new conference record of 174 feet, 5 inches. The following year, 1917, Liversedge established a new national collegiate record in shot put.

Liversedge posing for a 1916 Blue & Gold Yearbook photograph at the "California Oval" -- the track at California Field.

1917 was also the year the United States entered World War I, leading Liversedge to leave Berkeley at the end of his junior year and enlist as a private in the United States Marine Corps. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant in September 1918, and sent to France, arriving just before the war ended in November. When the United States Navy sent a group of athletes Antwerp, Belgium to participate in the 1920 Olympics, Liversedge was among them. He competed in shot put against two great Finnish athletes. Vin Porhola took the Gold Medal, with a throw of 14.81 meters, and Elmer Niklander just edged Liversedge out for the Silver with a throw of 14.155 meters, to Liversedge's throw of 14.15 meters. But Liversedge was pleased to bring home a Bronze Medal for the United States.

Liversedge decided to make his career in the Marines, and made steady but slow progress up the ranks, which was all that was possible in the tiny peacetime military which existed between the wars. He returned the the Bay Area in the mid-1920s when he was stationed at Mare Island in Vallejo for two years, and again from 1930 to 1932, when he was aide-de-camp of the Commanding General of the Marine's Department of the Pacific, in San Francisco. Among many other postings, Liversedge spent time in Haiti and two years in China. He continued his participation in sports, playing football on a Marine Corps team. While in China in the late 1920s, he was placed on detached duty to act as a boxing coach to the Third Marine Brigade and also participated in the International Track and Field Meet in Shanghai.

By the time the United States entered World War II in December 1941, Liversedge was a Lieutenant Colonel. He was promoted to full Colonel a few months later, taking command of the Third Marine Raider Battalion and, later, the newly organized First Marine Ranger Regiment. He led his regiment during the New Georgia campaign in the Solomon Islands in 1943, and was awarded his first Navy Cross for "gallantly leading his troops through dense jungle into combat against a fanatic enemy long experienced in jungle warfare, commanding the assault with cool and courageous determination."

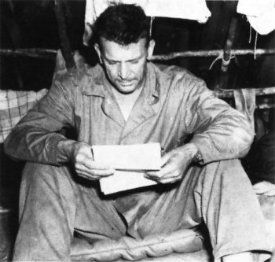

Col. Harry Liversedge, during the New Georgia campaign.

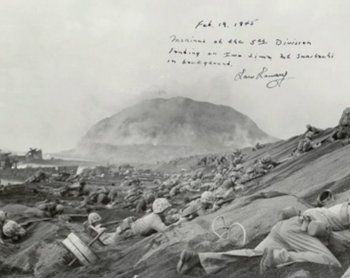

In January 1944, he was transferred to the Fifth Marine Division, and given command of the 28th Marines, the unit ultimately chosen to lead the assault on the volcanic island of Iwo Jima in February 1945. It would become one of the most famous battles of the Pacific war, and the bloodiest battle in the history of the United States Marines. When the Marines first landed, they were pinned down on the open beach by deadly Japanese fire. When Liversedge and his second-in-command, Lt. Col. Robert Williams, landed twenty minutes after the first wave, they found their men burrowed into the volcanic beach sand, under heavy fire. Lt. Greeley Wells described the scene: "We were all loaded down with equipment, and the beach sand was volcanic and very hard to walk in. The artillery fire was getting pretty heavy at this point, there was machine-gun fire." Men were being killed all around him, "so it was obvious to me that we had to get out." Wells described what happened next:

About that time we were all lying together, just hordes of men -- the beach was literally covered with men -- and suddenly I saw Liversedge and Williams walk up the beach as if they were in the middle of a parade. Williams had his riding crop, which was slapping on the side of his leg, both of them were urging us on, saying, "Get up! Get up! Get off the damn beach!" It was an amazing thing. They walked the length of that dog-gone beach yelling at the men, and the Marines just did it -- they got up and started to move. Of course it jarred me as well, and I got up, and we got over the high ground. Suddenly we were in the middle of this damn battle and there were casualties like nothing you'd ever seen.

Harry Liversedge's Marine regiment on the beach at Iwo Jima, minutes after the first landings on February 19, 1945. Mount Suribachi is in the background.

The Americans knew they had to take Mount Suribachi, the island's volcanic mountain and the only high ground. The Japanese had spent months fortifying it with heavy artillery protected by steel doors, and building a network of reinforced tunnels inside the inactive volcano. Tremendous fire rained down on the Americans from the mountain. Col. Liversedge was given the assignment of taking Mount Suribachi. And on February 23, 1945, a patrol of five Marines and one Navy corpsman, under Liversedge's command, made it to the top of the mountain. As Liversedge watched through his field glasses, his men raised an American flag. Joe Rosenthal's photograph of that moment is among the most famous ever taken.

Mount Suribachi, February 23, 1945.

While the sight of their flag flying on Mount Suribachi cheered the American soldiers, sailors and Marines tremendously, the fighting on Iwo Jima would continue for another 31 days. The Japanese entrenchments and network of tunnels allowed them to keep fighting, and their determination to fight to the death made the casualties on both sides appalling. In the end, 70,000 Americans fought on Iwo Jima. 6,821 were killed and 19,217 were wounded. Of the 22,060 Japanese defenders, 21,844 died, either in combat or by suicide, while only 216 eventually surrendered. Somehow Harry Liversedge emerged from the battle without a scratch. According to Captain (later Major General) Fred Haynes, he also emerged with the reputation as "one of the greatest combat commanders in the history of the United States Marine Corps." Another of Liversedge's young officers, Lt. John McLean, described him this way:

Liversedge was a superb field commander, greatly respected by his troops. Col. Liversedge was never bombastic or flamboyant -- no macho displays. He was self assured and quietly confident, born of his experiences as a successful commander in earlier Pacific battles. He enjoyed the complete respect and confidence of his troops. But there was more to him than that. The colonel had a sense of humanity and a deep regard for his men, which inspired all to perform to the best of their ability. . . . I venture to say that there was not a man in the 28th Regiment, from the highest-ranking officer to the lowest private, who would not gladly have followed Col. Liversedge to hell and back. And at Iwo Jima every one of them did.

Col. Harry Liversedge, left, and his executive officer, Lt. Col. Robert Williams, during the battle of Iwo Jima.

For his heroism at Iwo Jima, Liversedge was awarded his second Navy Cross, with the following citation:

The Navy Cross is presented to Harry Bluett Liversedge, Colonel, U.S. Marine Corps, for extraordinary heroism as Commanding Officer of the Twenty-Eighth Marines, Fifth Marine Division, in action against enemy Japanese forces on Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands, from 19 February to 27 March 1945. Landing on the fire-swept beaches twenty-two minutes after H-Hour, Colonel Liversedge gallantly led his men in the advance inland before executing a difficult turning maneuver to the south preparatory to launching the assault on Mount Suribachi. Under his inspiring leadership, his Regiment effected a partial seizure of a formidable Japanese position consisting of caves, pillboxes and blockhouses, until it was halted by intense enemy resistance which caused severe casualties. Braving the heavy fire, he traversed the front lines to reorganize his troops and, by his determination and aggressiveness, enabled his men to overrun the Japanese position by nightfall. By this fighting spirit and intrepid leadership, Colonel Liversedge contributed materially to the capture of Mount Suribachi, and his unwavering devotion to duty throughout was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

Following the war, Liversedge was promoted to Brigadier General. He spent some time stationed in Japan and Guam, and also at Camp Pendleton in California. In 1950, he was placed in charge of the Marine Corps Reserve. He died unexpectedly of a heart attack on November 25, 1951 at the age of 57, and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. In 1996 he was inducted into the University of California Athletic Hall of Fame.

Brigadier General Harry B. Liversedge, USMC

GO BEARS!

|

| Plaque at Liversedge Field Camp LeJeune |

|

| Marine Rugby Team in Tientsien China in the 1920s Harry is on the extreme right second row. |

BGen Liversedge died at the National Naval Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland, on November 25, 1951. He is buried Pine Grove, California.

Awards & honors

His military awards include:

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment