1960

SUMMERTIME

Episode

IV: Hi

Ho! Hi Ho! It’s off to Work We Go!

Before

we (Barrie, Pat, Denis, and I) left the Mountain View home, we had

all been hired for jobs of various kinds, one of which was fruit

picking. To be fruit pickers we needed transport, as the orchards

were a considerable distance from us, and the public transport system

was virtually non-existent. Barrie, the only member of the clan who

possessed folding money, was the purchaser of our transport, a

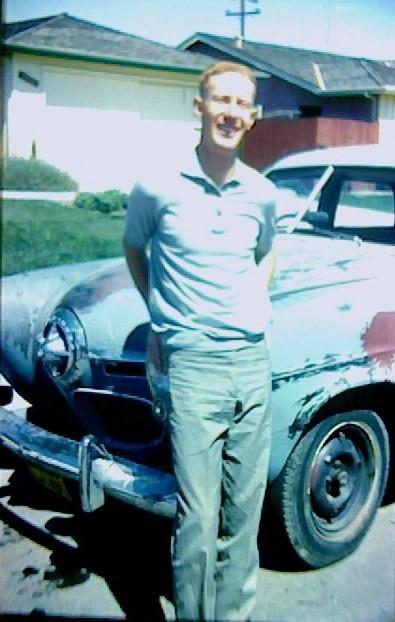

magnificent 1951 Studebaker, for the princely sum of $45. One picture

is worth a thousand words, and here are two photos of our pride and

joy. I’m featured in one, and Barrie, in the other.

Note

the oil spilled on the road in the first picture. There was no

bargaining when our car was purchased. It was a take it or leave it

proposition. The dealer did offer to help us get it off the lot if

necessary, but we managed to get it moving without a clutch start.

There were, however, two major problems with our newly acquired

asset.

- It’s consumption of oil exceeded its petrol consumption. What didn’t blow out in a large plume of smoke would drip onto the road (another complaint registered by the Christiansons).

- Its top speed was 50mph, and that was on a downhill slope.

Both

deficiencies resulted in traffic fines. The first was when I was

driving on the Bayshore Freeway. (Yes, by this stage I did have an

American drivers’ license.) A police motorcycle came through the

smokescreen coughing and spluttering and pulled me over. He issued me

a ticket for not reaching the minimum 50mph speed limit on the

freeway. I disputed the charge as I explained that it was the car’s

fault and not mine. He examined the registration slip and issued the

ticket in the name of the owner, Barrie Almond. I hear rumours that

Barrie is still being sought by the Californian police. I do know for

a fact that they sent follow-up notices to him at the University of

Houston. Tsk! Tsk!

The

second fine was for polluting the atmosphere and included a notice to

repair the car to stop the smoke. This was best attended to, we

thought, by not putting oil into the car. Our method did work: the

smoke plume was substantially decreased, and the oil spots on the

road were largely eliminated. Of course, the inevitable happened. On

a bright summer’s day the motor seized up, and the “Studie”

came to a complete halt on a suburban road. There it stayed until an

enterprising scrap metal merchant offered $10 for it, no questions

asked. It was too good an offer to turn down, and that fine piece of

automotive engineering was no longer ours ─ or Barrie’s, to be

precise. When the seizure occurred, Barrie was already well on his

way back to Houston on a Greyhound bus, and, as far as I know, he has

never been reimbursed by the one who pocketed the $10.

When

we took possession of the Studebaker, about a week after we arrived

in Mountain View, the fruit picking season began. Four of us, Denis,

Barrie, Pat, and I, drove to one of the apricot orchards seeking

work.

The

deal, as best I remember it, was that we would be paid 10c for every

bucket of apricots we picked. Those picked, we were told, must be

fully ripe, not green. As nature would have it, the ripe apricots

were at the top of the tree when the season commenced. To access the

top we were each given a twenty foot ladder. Having hooked your

bucket to the ladder, the technique was to balance on the top rungs

and use both hands to pluck the ripe apricots. Speed was all

important if you wanted to make any type of money in the fruit

picking business.

From

the ground level a twenty foot ladder doesn’t look all that high. I

think it’s because your head is already six feet off the ground ─

only fourteen feet more to the top. But when your head is four or

more feet above the top of the ladder, it can be a fearful sight to

glance down some twenty-four feet to the ground while balancing

without a handhold. We watched the Mexican workers go at it before we

tried picking fruit ourselves. They shinnied up the ladders and, with

both hands working like machines, were down again in a breath or two

with a bucket of choice apricots ready to be tallied.

Our

ascents were far more cautious, and releasing your hold on the ladder

to pick with both hands was mind-numbing. After four or five hours

and precious few buckets to our credit, Denis and I were fired. Denis

was told he was far too slow, and the field manager accused me of

eating more than I was picking. He wasn’t wrong there. The apricots

were delicious…and free. But in the days that followed I did pay

the price of consuming an excessive number of the little beauties.

I’ll leave that bit to your imagination.

Towards

late afternoon Pat was dismissed. Apparently, he fell off the ladder

and broke some limbs (tree limbs, that is) on the way down. Barrie

managed to keep his job until he was caught shaking the tree, a

method that deposited both ripe and green apricots on the ground. It

was a technique that did improve his productivity, but arranging the

green fruit on the bottom of the bucket and covering it with the ripe

fruit wasn’t considered kosher.

So

it was that, come late afternoon, we were all unemployed again. In

those days there was no redundancy payment or even worker’s

compensation for Pat’s injuries. Even if there had been such a

thing, we would probably have decided that in our particular case,

suing for wrongful dismissal may not have been worth pursuing.

But

the commencement of the fruit picking season also meant that the

fruit canneries started hiring casual workers to process the newly

picked fruit. So Denis and I joined the mass of humanity outside the

gates of the two local canneries: Libby’s and Richmond-Chase. We

lined up at separate canneries, hoping to display our talents to a

wider market.

Denis

was successful. I guess he looked more Mexican than I did. After

awhile, I figured out the way into the system. Jimmy Hoffa’s

Teamsters’ Union controlled the canning industry in California, and

you had to belong to the union before you could be rostered on by the

company. Here’s the “catch 22”: you could not belong to the

union unless you were employed by the company. Much later I figured

out that you had to slip the union delegate $25 to break the nexus.

But even if I had known earlier, I didn’t have $25.

With

nearly half the summer gone, I was like Orphan Annie. Barrie secured

full-time work at Track

and Field News;

Pat got a job with an insurance company; Al was on his way to the

Olympics; lovesick Ollan was getting ready to head east, and the

banana and the dime had long since disappeared. My total income for

the summer was half a day’s pay for picking fruit and a few hours’

part time work stuffing envelopes at Track

and Field News.

I was home alone, the only unemployed member of the household and its

sole dependant. So what to do? Repairing the table I had demolished

wasn’t income producing, and summer casual employment was now

non-existent.

I

started looking in the employment section of the paper for permanent

positions, thinking, “Well, what the heck? I’ve got to get some

work.” I was living off my mates, and none of them were exceedingly

wealthy. In one of the local papers I came across an advertisement

for a paint salesman for a hardware store in Palo Alto. Now that was

something I could do. Selling Bibles? No. Picking fruit? No. But

selling paint? Yes! For five years I had worked in a paint factory as

a sales clerk, and before I had left Australia for the United States,

I had been promoted to a position as junior salesman. I knew paint

technology extremely well, having completed a course at night school

and worked in the paint laboratory.

I

called, was interviewed, and got the job, starting immediately. My

credentials were impeccable for what they wanted. But my credibility

as a fulltime employee was not the best. I have to say that I did not

tell the truth about my intentions to remain in California. I flat

lied. And I still have pangs of remorse about deceiving the wonderful

couple who employed me. My dilemma was that I knew I could not

survive the following year at university without at least some money

in the bank for personal expenses. At the interview I had said that I

was an Australian student who had completed one year of college and

had decided that one year was enough study. Instead of continuing

with my education I had applied for American citizenship and planned

to stay permanently in the United States.

The

hardware store was Hubbard’s Paint, located in a small shopping

centre north of the Bayshore Freeway. I think the suburb was North

Palo Alto. The owners, Mr and Mrs Hubbard, were well into their

sixties and looking to limit their time in the store. Paint was the

main product sold, but they also stocked a full line of hardware. Mr.

Hubbard was less knowledgeable about the paint business than he was

about hardware in general, so when I showed up with a head full of

paint technology, I was like manna from heaven.

With

half the summer gone, the best I could give them was seven weeks, and

I have never put in a more earnest or honest seven weeks’ work than

there at the hardware store. I mixed paint, advised buyers about the

type of paint best suited to their need, explained the correct

techniques for preparing the surface, and raced up and down the

Bayshore Freeway in the company’s delivery truck. At the end of

each day, I could reconcile the takings with the sales dockets and

close the shop.

Exemplary

work practices have their downside. After five weeks of labour that

was way beyond the call of duty, Mr. and Mrs. Hubbard told me that

they were hoping to slowly withdraw from the day to day activities of

the business in order to begin enjoying the fruits of partial

retirement. As they had no children, they wished to know if I would

be interested in buying, or more likely, earning my way into the

business as a partner.

What

to do? Telling them that I was leaving in two weeks to go back to

school would be hard enough. Now that they wanted me to go into

partnership with them, I couldn’t face the prospect. I don’t mind

telling you that I did not feel really good about this. Call it

cowardice if you like. I could not come out and say that I had

deceived them. I just did not have the courage, and more importantly,

I didn’t want to cause any hurt or feelings of betrayal –

especially as they had come to trust me implicitly and wanted to

share their business with me. Instead, I compounded my earlier deceit

with a new fabrication.

With

one week to go, I said to them that I could not accept their generous

offer of a junior partnership in Hubbard’s Paint as the United

States government had drafted me into the Marines. I explained to

them that, as I was unemployed when I applied for citizenship, I was

a candidate for military service when citizenship was granted.

Moreover, I said, the notice required me to report in one week’s

time to the Quantico Military Base for basic training, after which I

would be attached to the Marines for two years.

One

week later I was on the Greyhound bus for “Quantico” (via

Abilene, Texas). An earlier epistle revealed my encounter with the

Border Patrol, so I won’t recount it here.

As

for my one year of military service, I never did quite make it to

boot camp. However, I did have a friend from college who, after

graduation, signed up with the Marines and was stationed at Quantico.

I felt so bad about what I had done that, for a little over a year, I

mailed him a few cards and a letter addressed to the Hubbards and

asked him to forward them, postmarked Quantico. None of them had a

return address, of course, as I did not want letters arriving at

Quantico addressed to Private first class John William Lawler.

Towards

the end of this one year of my correspondence, the Vietnam War was

getting underway, and I considered writing one last letter to the

Hubbards informing them that I had paid the ultimate price for my

American citizenship but that had an obvious flaw. In the end, I just

stopped weaving my “tangled web.”

Two

years later I was back in the Palo Alto area for another summertime

work stint, and I drove past the paint store. The name “Hubbard’s

Paint” was still there, but I did not make my presence known. I was

not up to concocting another fantastic tale and could not face

telling them the truth.

So,

dear reader…what do you think? Were my actions utterly deplorable,

and will I be removed from your next years Christmas card list? And

consider for a moment what you would have done once your half share

of the banana and the dime was gone.

I

can only hope that my grandchildren do a better job than I did when

they have to face what appears to them to be an insurmountable

problem.

The

next summer the saga continues:

- Driving a yellow cab from New York to Roswell, New Mexico…

- Working on a missile base with a construction crew that included a known murderer…

- Busboy duties at the University of Houston cafeteria while being pursued by the campus police.

The

prospect of making the summertime sagas into a TV series was

considered and rejected by the major networks on the grounds that the

stories were too unbelievable and would certainly not get a “G”

rating. Disappointing, as I was hoping Russell Crowe might want to

play the lead.

No comments:

Post a Comment