Introduction

By every standard, America America Texas

In less than 40 years, The University

of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) grew to among the largest 60 universities in the

United States America San Antonio San Antonio for the All American

City

Growing

Up

My life began in a quiet barrio in the Westside

of San Antonio in the 1940’s. Three of my grandparents had emigrated from Mexico South

Texas . Only one of my four

grandparents had attempted primary school.

Prior to moving to San Antonio San Antonio and they met when the two families joined to

pick the cotton crops of South Texas .

Few immigrant children growing up in San Antonio

Dad left school, at age 16 where upon he opened

up a shoe shine stand downtown. After

several years, he moved on to a job working in a wholesale poultry

business. At the age of 19, the owner of

the poultry business offered to sell his business for $200. With the help of his dad and uncle, they

bought the business. At this point, Dad

decided to re-enroll once again in school and managed to earn his high school

degree in night school when he was 23 years old. When Dad finished high school, he married my

Mom, Alicia. Their first house was in

the housing project in the Westside of San Antonio. While living there, America went to war following the Japanese

attack on Pearl Harbor . Soon after, Dad enlisted in the Army Air

Corp. Mom and two kids, including me,

went to live next to my grandmother’s house.

My Dad returned from the war after serving in the

Philippines Sacred Heart

Catholic School Sacred Heart

Catholic School

The majority of my classmates from the Westside

community of San Antonio

When my dad returned from the Armed Services in

1945, he decided to sell his share of the family wholesale poultry

business. He took his new investment and

purchased a small grocery store that was going out of business. In our “mom and pop” grocery business,

everyone pitched in. I worked long hours

in the family store, but I realized later that that hard work paid off in many

ways.

|

| Golden West |

At the store, although I met a lot of people, I

got to know only two who had attended college.

Both of them had attended college on the GI Bill, and for years these

educated individuals were role models for me.

I later learned that in most southwestern states, less than three

percent of Mexican Americans completed college.

My path to becoming a first generation college

student took many unusual twists. Certainly

key to my drive of completing high school and attending college, the path

started in middle school. There, I was

rewarded with a very good mentor, Coach Bill Davis, who recognized I had

potential in running and constantly pushed me to participate in sports.

On the Westside, the “cool dudes” were tough

kids, some of whom were already joining the barrio

gangs. At the time, many of the young

teens aspired to be rebellious, and machismo

was exalted, if not dignified. As a

consequence, many of the young rebels were often kicked out of school for

fighting and misbehavior. Peer pressure

to join the gangs was intense. Those who

did not join were often ostracized. I

was lucky that I attended Horace Mann, a middle school where gang problems were

minimal.

There were very few Latinos in our middle

school. My parents had wanted me and my

brother to attend a school on the Northside because of the gang problems in our

Westside neighborhood. Using the address

of a family friend, we enrolled in Horace Mann, a large Anglo school on the

Northside of town, which was accessible to us only by city bus. The school was 98 percent Anglo with only a

handful of Latino students enrolled there in the 1950s.

I was fortunate to be mentored by a kind teacher,

Mrs. Randolph, who made it her goal to keep me out of trouble. She became instrumental in keeping me

focused, and with her guidance I was assigned to different jobs on campus. I served as a volunteer library assistant;

and for free meals, I worked in the dining hall cafeteria cleaning and washing

dishes. The librarians encouraged me to

read, and while working in the library, I became interested in reading

biographies.

While Mrs. Randolph was my academic advisor,

Coach Bill Davis served as my athletic mentor.

He was an intelligent, caring individual, with an outgoing

personality. These mentors were

influential in my early years and convinced me that every successful leader has

benefited from good instruction by caring teachers and positive

mentorship. Each mentor was different

and each contributed in his or her own way to personal development.

In that era, the major battles over civil rights

emerged. From the time of statehood in

1846, Texas Union as a

slave state and joined the Confederate forces in the Civil War. Jim Crow resided in Texas ,

and the City of San Antonio Texas

Coach Bill Davis at Horace Mann

Middle School

My dad was also involved in the Mexican-American

civil rights struggle. He had returned

from his military service to witness firsthand blatant discrimination and

injustice in his home town. In the Army

Air Corp, he became familiar with the inequality toward Black soldiers. He taught us that we would likely experience

discrimination, and we must also never participate in discriminating against

anyone. He taught us to value equality

and justice.

As young boys, we witnessed firsthand the

struggle for residential integration.

Our first home had been on El

Paso Street Guadalupe Street Guadalupe

Street Durango Street

I might add that I had known little about

discrimination growing up because I lived in a barrio with only Hispanic

kids. I first witnessed discrimination

when we moved to Prospect Hill. We saw

and heard many discussions of white flight as we moved into our first real

home. In less than five years all the

Anglo neighbors had moved out of that neighborhood. Our street became more and more Latino, and

in a few years, it was a total Latino community. Prospect Hill attracted many of the Latino

middle class; families with incomes of more than $3,000 a year. On our street lived the Davilas, a family who

sent a son to college. Other

recognizable leaders coming from our street included Henry Cisneros, later

Mayor of San Antonio and U.S. Housing and Urban Development Secretary, and the

Briseño family. Alex Briseño became the

city’s first Latino City Manager and his brother Rolando, a prominent artist,

lived two blocks away. On the same

street lived the outstanding artist Jesse Trevino and his family. A block south lived Hope Andrade, later the

first Hispanic woman Texas Secretary of State; and one block south lived Lionel

Sosa, who in the 1980s founded the largest Latino media company in

America.

During the post-Brown decision of 1954, school

segregation declined, and students were able to enroll in any of the city’s

public schools. I decided to attend San

Antonio Vocational and Technical

High School

I entered high school knowing little about career

options. My dad was counting on me to

run the grocery store after he retired.

Thus, initially, I knew that business courses would serve me well. But after I started running track, the option

of attending college on a track scholarship quickly changed my mind set. In the tenth grade, I won every race I

entered up to the State Championship.

Over the next two years, I won every race including two State

Championships. My successes in

athletics, and the fact that I held the nation’s second fastest time in the

mile, opened new doors. I had known

since the tenth grade that I would be attending college on a track

scholarship. I had many scholarship

offers from out-of-state universities, but my family convinced me to select a

university close to home. While I had

been a good student at Tech H.S., I left for college in the fall of 1962 with

feelings of joy and trepidation. I knew

that only a handful of Latinos were enrolled at UT Austin, and only one other

Latino of more than 200 scholarship athletes joined me that year.

While I had given college a lot of thought during

my last year in high school, I had very little understanding of what the

college experience would be like. No one

in my family had gone away to college, so I never discussed with anyone what I

would major in or what courses I should take.

The first year was especially challenging for me. While I studied constantly, I did not seem to

make much progress. Fortunately, I

learned from my classmates how to apply good study habits. As a result, I began to see positive results.

|

| Racing in England with Alan Simpson and John Wetton |

Because of interest in teaching history, I turned to education courses with intent to both teach and coach at the high school level. Upon graduation and newly married, my wife and I left for

I learned from athletics that self-assessment was

as important as preparation and training.

As a distance runner, I had to constantly assess my capacity for

training, as well as my need for fuel, water, and rest. I had to determine whether speed was a

strength or liability in certain middle and long distance races. Competing in distance running also taught me

lessons about preparation, determination and postponing gratification.  The title of a new book, Heart, Smart, Guts and Luck pretty well sums up what I was learning

from my running experience. However, an

injury before the

The title of a new book, Heart, Smart, Guts and Luck pretty well sums up what I was learning

from my running experience. However, an

injury before the U.S.

from some of our email conversations

The title of a new book, Heart, Smart, Guts and Luck pretty well sums up what I was learning

from my running experience. However, an

injury before the

The title of a new book, Heart, Smart, Guts and Luck pretty well sums up what I was learning

from my running experience. However, an

injury before the from some of our email conversations

George.

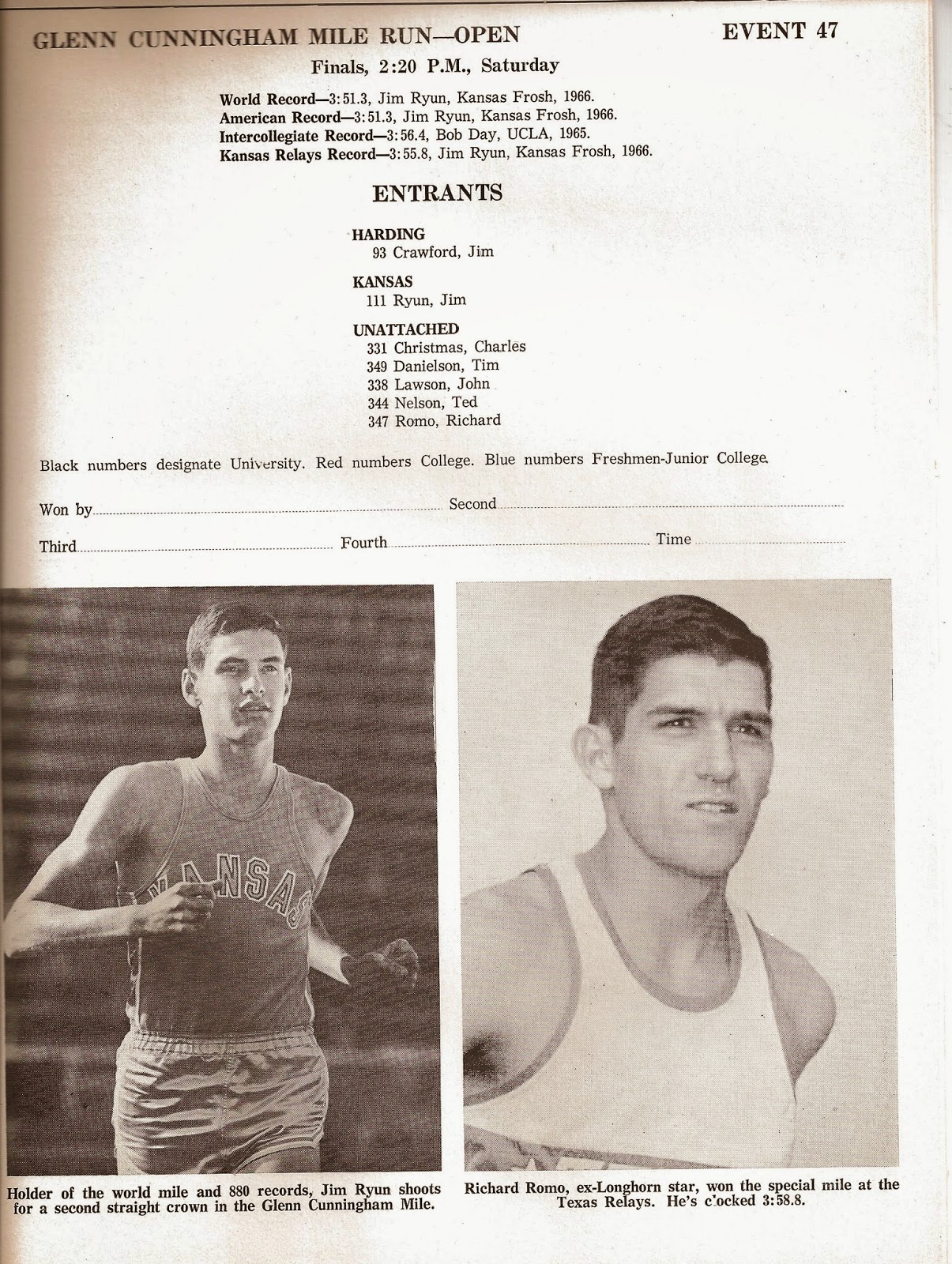

Well, small world. No doubt we ran at the Texas Relays at the same

time. I remember Lawson and Dotson, and recall the fine runners from

the midwest. One of the best was Robin Lingle from Missouri. Wonder

what happened to him. Thanks for your interest in my story.

My running days are over. I do lots of walking. Best, Ricardo

time. I remember Lawson and Dotson, and recall the fine runners from

the midwest. One of the best was Robin Lingle from Missouri. Wonder

what happened to him. Thanks for your interest in my story.

My running days are over. I do lots of walking. Best, Ricardo

Apr 20

|   | ||

Ricardo,

Robin Lingle died several years ago from a lingering illness.

I don't recall exactly what that was. His was an interesting

story having started out at West Point. He left there after a

cheating scandal, because as a matter of honor he would not

rat on his comrades. He was not accused of cheating.

I spoke to him several times when we competed against Missouri.

He was very open and friendly but still carried that military

bearing about him. Very disciplined, and his presence was a

big influence on that team. He graduated with an engineering

degree then turned to teaching in the private secondary school

in the East where he had been a student. Taught there his full

career. He was in the Jerry Thompson mile when John Camien

upset Dyrol Burleson.

I don't recall exactly what that was. His was an interesting

story having started out at West Point. He left there after a

cheating scandal, because as a matter of honor he would not

rat on his comrades. He was not accused of cheating.

I spoke to him several times when we competed against Missouri.

He was very open and friendly but still carried that military

bearing about him. Very disciplined, and his presence was a

big influence on that team. He graduated with an engineering

degree then turned to teaching in the private secondary school

in the East where he had been a student. Taught there his full

career. He was in the Jerry Thompson mile when John Camien

upset Dyrol Burleson.

That's amazing that your mile record held so long at UT.

It also is interesting that it has been in the hands of a Latino for

so many years with Joe Villarreal, yourself and Leo Manzano.

Is Villarreal still alive? I'm interested too that you were not in the

68 Olympic trials. Were you injured or had your career taken you

away from the hard training and racing?

It also is interesting that it has been in the hands of a Latino for

so many years with Joe Villarreal, yourself and Leo Manzano.

Is Villarreal still alive? I'm interested too that you were not in the

68 Olympic trials. Were you injured or had your career taken you

away from the hard training and racing?

Happy Easter, George

George.

I wish Robin (Lingle) had stayed at West Point.

I finished 2nd to him several times at major Relays,

including 1964 Tx. Relays and Kansas R. He was quite a

runner—and had a great finish.

I finished 2nd to him several times at major Relays,

including 1964 Tx. Relays and Kansas R. He was quite a

runner—and had a great finish.

I knew Joe V. well in the late 60s—lost touch after

Mexico '68. We hosted him when the Mexicans came

to Los Angeles in 67. —he was the Distance coach for

the Mexican team in 68. I Have not heard about him

for decades.

Mexico '68. We hosted him when the Mexicans came

to Los Angeles in 67. —he was the Distance coach for

the Mexican team in 68. I Have not heard about him

for decades.

In May 64, I ran a mile race in Houston and finished one

spot ahead of Jim Ryun. That month, I took a job loading

beef at the meat packing packing district in SA—starting

work at 2am and ending at noon. I also enrolled for night

summer classes—and it was all predictable. I messed up

my training schedule and found that training at 5pm in

105 degree weather was nearly impossible. In June, Jim

won the 3rd spot on the Olympic team.

spot ahead of Jim Ryun. That month, I took a job loading

beef at the meat packing packing district in SA—starting

work at 2am and ending at noon. I also enrolled for night

summer classes—and it was all predictable. I messed up

my training schedule and found that training at 5pm in

105 degree weather was nearly impossible. In June, Jim

won the 3rd spot on the Olympic team.

I was injured in feb. of 1965—got spiked in an indoor meet

in Ft. Worth—where we ran on dirt left over from the Rodeo.

It was a deep wound and my season was over. My last race

was in May of 1967 when I won the West Coast R. in Fresno.

The top ten milers, including Bob Day were in the race—with

the exception of Jim Ryun. With 150 yards to go, I felt a

tightness in my leg and lower back. I won in about 4:00.8—to

the great disappointment of the meet director—Wannamaker,

who thought I should have broken 4min. For the crowd.

I never could train again, and decided to go to graduate school

instead. It was a good decision.

in Ft. Worth—where we ran on dirt left over from the Rodeo.

It was a deep wound and my season was over. My last race

was in May of 1967 when I won the West Coast R. in Fresno.

The top ten milers, including Bob Day were in the race—with

the exception of Jim Ryun. With 150 yards to go, I felt a

tightness in my leg and lower back. I won in about 4:00.8—to

the great disappointment of the meet director—Wannamaker,

who thought I should have broken 4min. For the crowd.

I never could train again, and decided to go to graduate school

instead. It was a good decision.

George - thank you so much for covering Ricardo Romo's story. As I was reading it, I could only think of my father, Aristeo Ruiz Jr, who had the same up bringing in Austin. My father was such an athlete and military man and his discipline and encouragement helped shaped me in my athletic career. He had big hopes for me to go to University on scholarship since few in our family did and costs were a big concern for him. Unfortunately, my achievements didn't make it to that level. But as I was reading Ricardo's story and somewhat hear the disappointment in not making the Olympic team, I realize the glory is not in whatever ultimate goals we had aspired to but in the journey of simply participating in a great sport and becoming a better person from it.

Looking forward to the second part and will have to share this on FB for mi familia de Tejas :). Susan

No comments:

Post a Comment