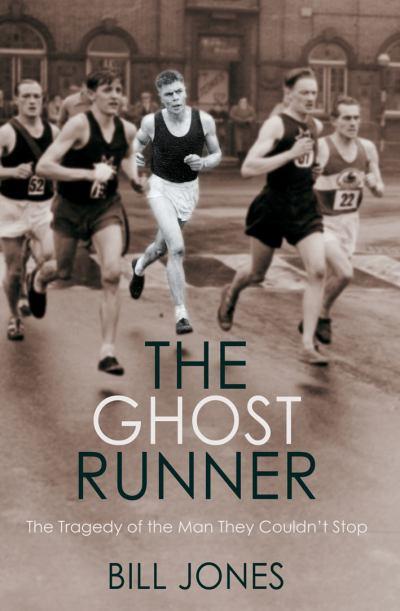

The third bit in this piece is the discovery of a book "The Ghost Runner" by Bill Jones. This is a biography of John Tarrant, another English working class runner of the 1950's who was banned for life having written in his application to be in a running club that he had received 17 Pounds expense money when he was an 'amateur' boxer prior to his running career. The banning failed to stop Tarrant from jumping into races all over England. At one time in his 'career' he set the world best times for 40 miles and 100 miles. A review of the book from the site The Iron You also appears in this posting.

Below, an excerpt from the BBC News piece on the first four minute mile:

But the most disconcerting side of the Iffley Road race is its glaring display of class division. Sport is well known to reflect, or to reinforce, social, cultural and political hierarchies. But the class stand-off was never better captured than in the Alf Tupper strip cartoons that appeared in British comics and papers between the 1950s and the 1990s. Alf was a brilliant miler, he was also a tough guy who worked as a welder, and was regularly insulted by his languid, upper-class fellow athletes - though Alf, of course, usually came out on top.

If we look a bit closer at the line-up on 6 May 1954, we'll glimpse just the same split: Alf against the rest. The mile event was part of a bigger competition between Oxford University and the national Amateur Athletics Association. Although we only ever see photographs of Bannister, Brasher and Chataway, there were six runners in all. Oxford had a team of two students who seem to have ended up fourth and fifth (though the crowding of the track at the end of the race made it hard to tell). They were supposed to have been a team of three, but - in a scatty undergraduate way - the third member turned up at the last minute to watch, not realising he was supposed be running, and hadn't brought his kit with him.

Hulatt may have had a great day in Oxford, but he was certainly the odd man out. Before the event Bannister came up to him and advised him to "run his own race" (it was probably a kindly gesture, but it could also have been telling him to stay out of their way). Afterwards, the Oxford students presumably went back to their colleges, the Bannister trio went celebrating and clubbing in London, Hulatt got his programme signed by Bannister, Brasher and Chataway and took the train back to Derbyshire.

I doubt that, outside his home village, Hulatt who died in 1990, will be a big part in our commemoration of the mile-record of 1954. Rightly, perhaps, the moment will belong to Bannister. But happily Alf Tupper is coming back into the limelight - in the sports magazine, Athletics Weekly, our wonderful working-class runner is just now starting a brand new cartoon series.

http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-27111860

April 26, 2012

Book Review: The Ghost Runner - The Tragedy of the Man They Couldn't Stop

This

is one of those books you just can’t stop reading once you started. The story is

well written and I was so involved I stayed up into the night to finish it. I

liked it so much that I keep talking about it to everybody.

In

other words, if you really want to read a true inspiring story: that’s your

book.

Because

this is

one of the most moving, engrossing, and tragic, tales in the history of

athletics I’ve ever heard of.

It's

the story of John Tarrant. A young teenager living in post-war Buxton (a city

close to Manchester in the UK) who at 19 years old gave up amateur boxing (after

some disastrous fights) and decided that he had what it takes to become a

successful runner.

Truly

believing in his potential, he applied to join a running club, naively declaring

an insignificant £17 of expenses reimbursement he got paid during his short

lived boxing career.

The

result was a lifetime ban from all domestic and international competitions. Why?

Because according to the regulations in force, the expenses reimbursement meant

that Tarrant had competed for money and this violated the strict codes

concerning amateurism in British athletics.

But

Tarrant was far from giving up his hope of becoming a runner. And in August of

1956 in Liverpool, he jumped from the crowd into a field of high-profile

marathon runners and started running with them.

After

leading for 15 miles, he keeled over and had to be carried off in an ambulance.

However, the local paper had gone to press while he was still in the lead and

the national press soon picked up the story; with

the Daily Express coining the nickname which would become his alter ego: the

ghost runner.

For

the next two years, Tarrant gate crashed races all over the UK, always running

without a number.

Audiences

at athletic meetings all over England became used to an extraordinary

sight.

A

tall man with unusually sunken eyes would hang around at the start dressed in a

long overcoat. As soon as the starting gun went, he would throw off his overcoat

and join in the race, despite the frantic efforts of stewards to stop him.

With

no number on his vest, he sped to the front of the field where he remained until

he either won, or - almost as often - collapsed from exhaustion.

Thwarted

by the nightmare of his ban, he ran at ever-longer distances, setting the world

record at 40 miles and then 100 miles. He fled to the USA and then South Africa,

where he ran as the only white in all-black road races ("a ghost in a nation of

ghosts") before cancer finally claimed him in 1975. He was aged just 42, and he

died unfulfilled and largely unknown.

Tarrant

ran up to 5,000 miles a year, always hoping he might prevent against the

system.

While

the men who controlled British athletics regarded Tarrant with deep disapproval,

the public was fascinated by his exploits.

In

the kitchen of their Hereford council flat, his wife counted the pennies. Out on

the road, he merely totted up the miles. Always the outsider, even where history

was concerned.

Tarrant

was a man driven by resentment. Brought up in a particularly rough children’s

home in Kent, he was beaten and bullied almost from the moment he could walk.

Running, it seems, was the only way he could outpace his demons.

By

now the athletics world had moved on and Tarrant was a forgotten man. He might

have stayed that way had not Bill Jones been given a copy of a memoir Tarrant

wrote shortly before his death. Idly, Jones began to leaf through it, and was

promptly gripped. ‘The

man,’

he writes, ‘has

been haunting me ever since’.

I

bet you’ll be moved by the life and death of this incredible man.

Read

this book, you will not be disappointed.

The

Iron You

is one of those books you just can’t stop reading once you started. The story is

well written and I was so involved I stayed up into the night to finish it. I

liked it so much that I keep talking about it to everybody.

In

other words, if you really want to read a true inspiring story: that’s your

book.

Because

this is

one of the most moving, engrossing, and tragic, tales in the history of

athletics I’ve ever heard of.

It's

the story of John Tarrant. A young teenager living in post-war Buxton (a city

close to Manchester in the UK) who at 19 years old gave up amateur boxing (after

some disastrous fights) and decided that he had what it takes to become a

successful runner.

Truly

believing in his potential, he applied to join a running club, naively declaring

an insignificant £17 of expenses reimbursement he got paid during his short

lived boxing career.

The

result was a lifetime ban from all domestic and international competitions. Why?

Because according to the regulations in force, the expenses reimbursement meant

that Tarrant had competed for money and this violated the strict codes

concerning amateurism in British athletics.

But

Tarrant was far from giving up his hope of becoming a runner. And in August of

1956 in Liverpool, he jumped from the crowd into a field of high-profile

marathon runners and started running with them.

After

leading for 15 miles, he keeled over and had to be carried off in an ambulance.

However, the local paper had gone to press while he was still in the lead and

the national press soon picked up the story; with

the Daily Express coining the nickname which would become his alter ego: the

ghost runner.

For

the next two years, Tarrant gate crashed races all over the UK, always running

without a number.

Audiences

at athletic meetings all over England became used to an extraordinary

sight.

A

tall man with unusually sunken eyes would hang around at the start dressed in a

long overcoat. As soon as the starting gun went, he would throw off his overcoat

and join in the race, despite the frantic efforts of stewards to stop him.

With

no number on his vest, he sped to the front of the field where he remained until

he either won, or - almost as often - collapsed from exhaustion.

Thwarted

by the nightmare of his ban, he ran at ever-longer distances, setting the world

record at 40 miles and then 100 miles. He fled to the USA and then South Africa,

where he ran as the only white in all-black road races ("a ghost in a nation of

ghosts") before cancer finally claimed him in 1975. He was aged just 42, and he

died unfulfilled and largely unknown.

Tarrant

ran up to 5,000 miles a year, always hoping he might prevent against the

system.

While

the men who controlled British athletics regarded Tarrant with deep disapproval,

the public was fascinated by his exploits.

In

the kitchen of their Hereford council flat, his wife counted the pennies. Out on

the road, he merely totted up the miles. Always the outsider, even where history

was concerned.

Tarrant

was a man driven by resentment. Brought up in a particularly rough children’s

home in Kent, he was beaten and bullied almost from the moment he could walk.

Running, it seems, was the only way he could outpace his demons.

By

now the athletics world had moved on and Tarrant was a forgotten man. He might

have stayed that way had not Bill Jones been given a copy of a memoir Tarrant

wrote shortly before his death. Idly, Jones began to leaf through it, and was

promptly gripped. ‘The

man,’

he writes, ‘has

been haunting me ever since’.

I

bet you’ll be moved by the life and death of this incredible man.

Read

this book, you will not be disappointed.

The

Iron You

2 comments:

I have put a link to this post on the PSU Track Alumni (Golfers)* site. I bought the book right after reading your post. Thanks for the great content on your site. It is amazing how much we compliment each other in covering vast swaths of the running and "other" worlds.

*The golf is only optional and there merely to confuse everyone. Our annual tourney is in May.

I'm filled with admiration for the guy.

Post a Comment