Beginning our 14th year and 1,200+ postings. A blog for athletes and fans of 20th century Track and Field culled from articles in sports journals of the day, original articles, book reviews, and commentaries from readers who lived and ran and coached in that era. We're equivalent to an Amer. Legion post of Track and Field but without cheap beer. You may contact us directly at irathermediate@gmail.com or write a comment below. George Brose, Courtenay, BC ed.

Once Upon a Time in the Vest

Monday, February 27, 2023

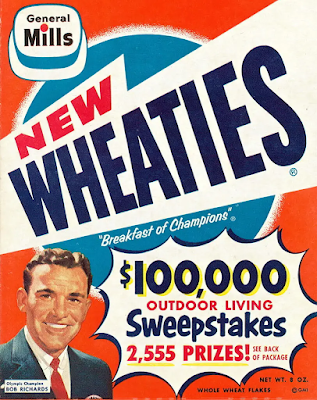

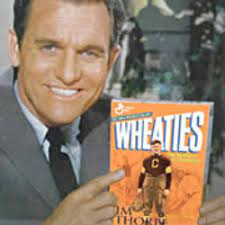

V 13 N. 25 Rev. Bob Richards R.I.P. at age 97

Saturday, February 25, 2023

V 13 N. 24 A Book Review "Path Lit By Lightning, The Life of Jim Thorpe"

"Path Lit By Lightning, The Life of Jim Thorpe"

David Maraniss, Author

Simon and Schuster

2022

659 pages

US $32.00 Canada $44.00

The title comes from Jim Thorpe's indigenous name Wa-tho-huk Path Lit by Lightning.

I rarely take a 600 page book home from the library, but when I saw that David Maraniss was the author, I could not resist. I had read his book Rome 1960: The Summer Olympics that Stirred the World and decided that I could not pass up this one about Jim Thorpe. Maraniss is an incredible sleuth and researcher and has come up with seldom heard, seen, or long forgotten material about the former nation's hero, the Sac and Fox athlete and survivor of the American Indian Residential School system that was self admittedly designed to 'kill the Indian and save the man'. In other words to make the indigenous children of the men and women who had fought the advance of the whites into thinking and acting like whites and integrating into the white society. This was accomplished by separating those children from their families, cutting their braids, forbidding them to speak their language, putting them in white men's and women's clothing, and taking up the white man's faith, about one step above General Billy Sherman's philosophy of 'The only good Indian is a dead Indian'. The former US army barracks at Carlisle, Pennsylvania was the place where the finished products would be turned back to white men's society. But this idea was not really coordinated with the laws being passed restricting citizenship, land ownership and other rights that the white men reserved for themselves. There were other schools as well around the western US doing much the same thing including Haskell Institute in Lawrence, Kansas which Billy Mills attended. Many survived, but many perished, and many were left with lifetime trauma that they passed on to their own children. At Carlisle there were at last count 186 graves of children who died at that institution. Repatriation of those bodies back to their homelands is gradually going on. To this day thanks to Jim Thorpe's third wife Patsy, he is not resting on his homeland but in a place called Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania that was organized by her, hoping to make some money from her conniving. Fortunately she didn't get any.

But getting back to Jim Thorpe's early life and athletic career, David Maraniss does an incredible job of tying together his track and football career at Carlisle, his Olympic triumphs, and the removal of his medals and the striking of his name from the Olympic record books. The details that Maraniss has put together are deserving to be read by any track nut. One is how Jim Thorpe was first introduced to track and field at Carlisle while he was walking past the team working out. Still wearing a pair of coveralls, he had a go at the high jump bar that had been set at 6' 1". He made it and the rest is of course history. He re-creates a lot of stories and separates the fact from fiction, because like any American hero there can be a lot of exaggeration and fog about events fifty years after the fact. He also writes about the other athletes who competed at Stockholm in 1912 including Jim Thorpe's school mate Lewis Tewanima, the Hopi who came to Carlisle not knowing a word of English in 1910, but who thrived on distance running and won a silver medal in the 10,000 meter race. He tells us about future General George Patton who while competing in the Modern Pentathlon was doped up with opium by the US trainer, a not uncommon practice in those days. Patton did not win a medal. The author does not spare his disdain of Avery Brundage in this book and keeps pouring it on every time Brundage is mentioned right to the end. Brundage was a member of the US Olympic team and competed against Thorpe in the Decathlon, but failed to finish, dropping out before the 1500 meters.

I had not known that Jim Thorpe lost his medals on a technicality. He had played summer baseball in North Carolina while an undergrad for two summers. He played under his own name, which many other college athletes did not do. They played under assumed names and were never banned from amateur athletics. The technicality by which he should not have lost his awards was that the International Olympic Committee said that any disqualification for breaking amateur rules had to be made within 80 days of the Olympic event. The news of his 'professionalism' was reported three months or 90 days after the Olympics. It was beyond the limit for a disqualification. That was how the medals (facsimiles) were eventually returned post mortem to his family. The original medals were 'lost' and the trophies are still stashed in some vault in Lausanne. The story came out when the High Point, North Carolina baseball club manager who coached Jim spent the off season at his sister's house in Connecticut and casually mentioned coaching Thorpe to an acquaintance, and that drew a sports writer to the house and the story was broken.

In the aftermath, both the president of Carlisle and the 'immortal' coach Pop Warner both claimed ignorance of the affair in order to preserve their own careers. It is something Warner could not possibly known about. Maraniss is not very sympathetic to Warner in the book.

Once DQ'd Jim Thorpe soon signed with the New York Giants baseball team and embarked on a world tour with the Philadelphia Athletics and the Giants. At the time his baseball skills were not up to major league standards. Problems with hitting the curveball. His signing was to help sell tickets. He was more popular on the world tour than the regular players which included stops in Japan, China, Australia, Egypt, Italy, and England where he played baseball before King George. Who knew anything about baseball in those countries, but they did know about Jim Thorpe, the greatest athlete in the world.

He went on to play for a number of major league teams and in 1919 his last year in the majors he was in Boston with the Braves at the same time Babe Ruth was in his last year with the Red Sox. One little known fact I learned was that the spitball was outlawed in 1918 or 1919 not because it gave the pitcher some advantage. It was outlawed, because the Spanish flu epidemic was in full force at that time and it was thought that the spitter might be a means of transmitting the disease.

Jim Thorpe's interactions with a myriad of celebrities all his life, his travels back and forth across the US trying to eke out a living with personal appearances and barnstorming teams rarely paid off in any way he had hoped are told in great detail. His career in the NFL is told including that he was the league president (a figurehead) for one year. The making of the movie about his life Jim Thorpe, All American starring Burt Lancaster is told in the book. He made very little off the movie, which was very popular at the box office, although he was hired as a technical consultant for the film. He also appeared in over 60 films mostly without lines and was paid very little.

I cannot even begin to tell the whole story or even begin to mention all the events that David Maraniss has written about. I can only recommend that if you walk past the book at your favorite store or the library, take it home and hope you haven't got anything else on your agenda that needs to be done before you finish the book. George Brose

Monday, February 20, 2023

V 13 N. 23 Track Athletes Who Were Also Peace Corps Volunteers

There are lists of politicians, writers, CEO’s, artists, and film people, even an astronaut who were in the Peace Corps in their early or later years. Over the years there have also been sports figures who have been PCV’s. They include an Olympic champion, a Boston Marathon champion, a famous coach, a not so famous runner but one who has been a long-time contributor to the sport, and a few more. Here is the list of Peace Corps Volunteers as well as track guys of whom I'm aware.

Bob Schul (Malaysia 1971-72)

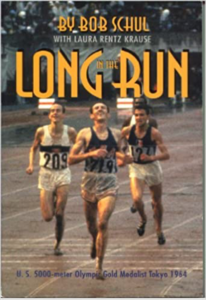

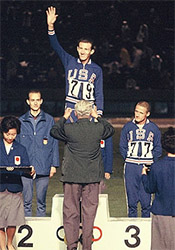

Bob Schul (center) 5,000m Gold Medal, 1964 Tokyo, Olympics

Let’s start with the Olympic champion, Bob Schul. Bob is the only American ever to win the 5,000 meters in the Olympics which he did in 1964. After college at Miami of Ohio and a tour in the Air Force, Bob would come under the influence of the great Hungarian emigre coach Mihaly Igloi, who doled out enormous quantities of repeat running intervals that only a few good runners could survive without permanent injury. And Bob thrived on Igloi’s workouts. By 1963 he was running world class times, and in 1964 he was just about unbeatable in the range of 3,000 to 5,000 meters. He would lead the US to first and third place in the 5,000 meters in Tokyo that year.

Bob returned home and continued to run, and by 1968 his career on the track was just about over. Bob was hired by the Peace Corps to be the national coach of Malaysia from April 1971 to April 1972.

In 2000, Bob published his memoir of running In the Long Run.

•

Amby Burfoot (El Salvador 1968)

Amby Burfoot

Anyone who knows much about marathoning or reads Runners’ World is familiar with Amby Burfoot. Amby won the Boston Marathon in 1968 and has been a long-time contributor to Runners’ World and is now senior editor. He has written a number of books on running including a history of the most influential women’s runners in the sport.

After he won Boston while still an undergrad student at Wesleyan College, that same year he saw an ad in The New York Times for a track coach in Ethiopia with the Peace Corps. It sounded like a divine intervention for him as Ethiopia was rapidly coming into the realm of world class distance running with Abebe Bikila having won the Olympic marathon in both 1960 and 1964. Where better to be  assigned as a distance coach? However, by the time Amby got in his application, the job had been filled, but he was offered and accepted a tour in El Salvador. He told me he was the only volunteer in his group assigned to live in the capitol, San Salvador, and coach young athletes. All the other volunteers were agriculture workers living in the countryside. (editor’s note: Abby Burfoot has written 6 books about running including First Ladies of Running.)

assigned as a distance coach? However, by the time Amby got in his application, the job had been filled, but he was offered and accepted a tour in El Salvador. He told me he was the only volunteer in his group assigned to live in the capitol, San Salvador, and coach young athletes. All the other volunteers were agriculture workers living in the countryside. (editor’s note: Abby Burfoot has written 6 books about running including First Ladies of Running.)

•

Tim Hickey (Tanzania 1964-66)

Unlike the first two PCV’s mentioned, Tim Hickey began making his name in the track and field world during his volunteer days and for many years after. His PCV service really set him on his career path. Tim grew up in the Midwest farmlands of Parker City, IN just outside of Muncie. He attended Ball State Teachers College (now Ball State University) and ran on their track team. After graduation he applied and got into the Peace Corps and was sent to Tanzania to be the National Basketball coach. When he saw the raw recruits he soon switched over to become the National track and field coach.

Unlike the first two PCV’s mentioned, Tim Hickey began making his name in the track and field world during his volunteer days and for many years after. His PCV service really set him on his career path. Tim grew up in the Midwest farmlands of Parker City, IN just outside of Muncie. He attended Ball State Teachers College (now Ball State University) and ran on their track team. After graduation he applied and got into the Peace Corps and was sent to Tanzania to be the National Basketball coach. When he saw the raw recruits he soon switched over to become the National track and field coach.

He had several runners who competed internationally for Tanzania including a sprinter Norman Chihota and a distance runner John Stephen. Stephen would become somewhat of a celebrity in the 1968 Mexico City Olympic film by Bud Greenspan. In the marathon, Stephen fell and injured his knee early in the race. But he got up and continued with some roadside bandaging and managed to finish the race at the tail end. Greenspan saw something in his effort to finish that endurance race that inspired him, and he featured Stephen’s arduous last strides toward the finish line.

When Tim returned home after his tour, he answered an ad for RPCV’s to teach in the public schools of Philadelphia. Many came; few stayed. Tim stayed for thirty years and served as coach at William Penn High School, an “inner city school” that met all the definitions which that term brings to mind. The school had no track and field facilities, so Tim coached his kids on the streets or in local parks. For many years William Penn was a powerhouse of Eastern and national high school track and field. The majority of his work was with the girls’ team and over forty of those girls won athletic scholarships to universities around the country. Today, Tim is revered in the track world in his adopted hometown. For most of that time he also served as director of the high school division of the Penn Relays, one of the three most important relay events in North America.

•

Bill Peck (Somalia 1965-66)

Bill Peck is less a household name in track and field than our earlier mentions yet to those who know him he meets all the criteria for respect and accomplishment in the sport.

Somalia was considered to be so difficult that assignments were only for 18 months rather than 24 months. There was only one working traffic light in the capital Mogadishu. As a sign of progress today there are probably no working traffic lights. And the Volunteers were told that they would be living on goat meat and tea for the duration, if they were lucky. During his service Bill organized the first national track and field championships ever in Somalia.

Recently he was honored by the Track and Field Writers of America (TAFWA) for his contributions to the sport.

Here is a transcription from TAFWA’s article about Bill in their July, 2019 newsletter.

2018 FAST AWARD TO BILL PECK — TAFWA is pleased to announce that Bill Peck is the winner of the FAST Award for 2018. We waited to announce this formally until we were able to locate Bill and present the award to him in person. Member Jack Shepard drove from his home in Los Angeles to Hemet, Calif., where Bill now resides, to make the presentation. (See photo.) An excellent runner in his own right, Peck began statistical compiling on his own in the early 1960s, probably while he was still an undergraduate at Occidental College in Los Angeles. He worked with data from early NCAA, AAU and Spalding guides at the beginning, and later prepared age-group lists for Starting Line magazine. In recent years he collaborated with Tom Casacky on the History of the California State Meet 1915 to 2006, a project he continues to work on. Because he does not have a car, phone or computer, he uses old-school methodology – transport by bicycle, record keeping by paper and pencil. As a runner, Peck was a scorer in the NCAA Championships for Oxy in ’60 (6th place) and ’61 (8th). He ran the Olympic Trials steeple in 1960 and had lifetime bests of 9:09.3 in that event and 30:38.0 in the 10k. He won the Mt SAC 10 in ’61 and is a member of the Occidental College Track and Field Hall of Fame. Prior to college, Peck served four years in the U.S. Marine Corps. He grew up near Laurel Canyon Boulevard, in the Hollywood Hills, and graduated from Hollywood High School. After college he taught history and coached at Eagle Rock and other high schools in the LA area.

Bill Peck and I were in training together at Syracuse University and would occasionally go on runs together. George Brose

•

Jerome McFadden (Morocco 1964-66)

Jerome “Jerry” McFadden was a scholarship runner at the University of Missouri in the mid 1960’s. He finished second in the mile outdoors at the Big Eight Conference in 1963. His best time for the mile was 4 minutes and 5 seconds. He went from Columbia, MO to Morocco after graduation where he served as a track coach.

Jerome “Jerry” McFadden was a scholarship runner at the University of Missouri in the mid 1960’s. He finished second in the mile outdoors at the Big Eight Conference in 1963. His best time for the mile was 4 minutes and 5 seconds. He went from Columbia, MO to Morocco after graduation where he served as a track coach.

Among his many talents, Jerry is also a prolific writer. Here is what Amazon says about him.

The following piece is by Jerome McFadden. It recounts his time working as a coach in Morocco. This is a condensed version of an article which appeared in “Runners’ World” in the 1970’s.

Peace Corps Coaches

In 1963 we were the second Peace Corps group going into Morocco but definitely the

first contingent of athletic coaches being sent out into the world. Our small crew

included three track and three basketball coaches, two swimmers, and two wrestlers.

The term “Coach” was a big word considering all of us but one had just graduated

from college or grad school in May or June of that year. The main part of our gang were

to be English teachers, surveyors, and female home economists.

After three months of training at Utah State University, (French, Arabic,

Moroccan culture, coaching techniques and psychological evaluation) we arrived in-

country in September. the track coaches were immediately spread out to Casablanca,

Rabat, and Marrakech. I inherited the 350 meter cinder track in downtown Casa,

adjacent to the Ministere de Jeunesse & Des Sports ((Ministry of Youth & Sports).

The infield was hard dirt, all of this surrounded by a mini three tiered cement

spectator stand The first look at the available equipment was equally discouraging: a

rusty set of hurdles, a warped discus, and a pock marked shot that looked like replica

of the moon. Welcome to African track & field, circa 1963.

But we did have night lights!

That was because training sessions were held Tuesday through Friday

evenings, 7:00 to 9:00pm, with competitions on Sunday morning. Similar to Europe, all

sports in Morocco were based on the club system rather than the scholastic system as

in the USA. Half of the league came on Tuesday and Thursdays, with the other half on

Wednesdays and and Fridays. Sunday mornings were for competitions.

The high jump and long jump all landed in the same pit, a large rectangular sand

box with varying degrees of lumpiness. There were three cross bars to work with on the

high jump, but we tended to save them for the competitions as they were easily bent or

broken. We practiced instead with a red elastic rubber rope tied to the uprights. The

elastic would throb and bob in gross exaggeration at at the slightness touch. If the

jumper landed solidly on it, the elastic would tangle around his legs and pull the

uprights down on top of him. Needless to say, pole vaulting was not on the program.

The starting gun for the runs was too wooden clappers attached by a leather

strip. Nothing dramatic but sufficient.

The Sunday morning competitions were adjusted to however many athletes

showed up, which meant most were half track meets, skipping those events of little

interest and giving special attention to record attempts. In spite of the third world

equipment, the runners were serious, dedicated, and competitive, filling the track on

the evenings allowed to them and giving their best efforts at the Sunday meets.

My chief value was my stop watch (provided to me by the Peace Corps), my two

running shoes (provided to me by the Peace Corps), and my availability to be at the

track whenever needed: stop watches were as scarce as the other equipment, the

shoes could be lent out in emergencies (stuffing newspaper into the toe section helped

for a better fit), and I had no where else to go as I was assigned to this track.

Two years is too fast for any coach. You concentrate on one race at a time, or a

series of races designed to bring your runners along, with the series of “one races”

making a season. Then you suddenly wake up to realize you haven’t accomplished all

you wanted with the kids and the two years are past. And two years is too short to see,

hear, smell, and touch all that there is to see, hear, smell, and touch in Morocco – the

snow capped mountains, the labyrinth of the medinas, the market places in the south

with their Berber dancers, snake-charmers, and story tellers.

But I made some lifelong friends and have some great memories, and was not

surprised when the African runners became a force to be reckoned with.

Jerome W. McFadden is an award winning short story writer whose stories have appeared in 50

magazines, anthologies, and e-zines over the past ten years. He has received a Bullet Award for the best crime fiction to appear on the web. Two of his short stories have been read on stage by the Liar’s League London and Liar’s League Hong Kong. His collection of 26 short stories, entitled Off The Rails was published in October, 2019, and was named a finalist for the 2019 Indie Book Awards and the Indie National Book Award (NIEA) and has outstanding reviews He is also the co-editor of the BWG Writers Roundtable e-zine.

— Amazon

Jerry McFadden and I ran against each other occasionally when he was at Missouri and I was at Oklahoma. He always smashed me on the track. We became reacquainted many years later when I was coaching in Quebec and some of my rival coaches were his former students in Morocco. They persisted in asking me if I knew where Jerry was. I didn't, but once the internet came into being I did find him and we've been good friends ever since. He has provided a lot of information and photos to this blog, especially anything relating to track and field history of France. George

Roy Benson, Philippines 1972

How a Peace Corps Volunteer was Instrumental in Helping Start the Running Boom

Roy Benson (Philippines 1972) had been an assistant track coach at the University of Florida when he joined the Peace Corps to coach that sport in the Philippines. Frank Shorter, the winner of the marathon at Munich credits Benson with helping him to prevail in that race which had the effect of kicking off the running boom in the US. First here is Shorter’s account of how Benson was able to assist him in that win.

1972 Olympic Marathon

Shorter lined up for the marathon only having run four marathons. He was a novice and not favored. Ron Hill of Great Britain and Derek Clayton of Australia had both run under 2 hours and 10 minutes which was two minutes faster than Shorter ran in winning the Fukuoka Marathon for the first time in 2:12:50.4 on December 5, 1971 . Though Fukuoka was regarded as the de facto world championships at the time, Shorter went largely unnoticed by the media.

“That was an advantage for me,” says Shorter. “I didn’t have any pressure.”

The Fukuoka was won with a strategy Shorter and Bacheler had developed in their 5,000 meter and 10,000 meter races. He trained his body to surge or accelerate for periods of time to gain an advantage over his competition, then recover at a fast clip, then do it again. At the time, marathons were races of attrition. Shorter’s strength were those surges so he decided his strategy was to use that strength early on to win.

Between the ninth and tenth mile, Shorter ran a 4:33 mile to break away from the field. He was off on his own. UF Assistant Track and Field Coach Roy Benson had taken the year off from his duties to coach the Philippines track and field team and was there on the course in Munich for the marathon race. He was part of a Peace Corps coaching program that Benson had seen in an advertisement in Sports Illustrated. Jimmy Carnes granted him the year long sabbatical with the caveat that Benson return back to the program after that year. Benson secured a bike and rode along through the throngs of people lining the course to provide updates to Shorter who he knew well.

“Yes, he was key, “recalls Shorter of Benson. “At 15 to 16 miles he let me know I had a minute and 12 second lead. Then he was able to get to the 19- and 20-mile marks and give me another update. I did the math in my head. I was running 5 minute miles and the others would need to run 4:48 to catch me. I knew that no one could do that and I just needed to hang on.”

Though Shorter knew he had the win in hand, when he entered the stadium for the final lap, he was met with a crescendo of boos and catcalls. A German student, Norbert Sudaus, had jumped into the race and arrived some 35 seconds earlier than Shorter. The catcalls and boos were for Sudaus after the crowd learned that he was an imposter.

“It bothered others more than it bothered me, “Shorter says. “I knew no one had passed me and I had won.” His victory margin was by more than two minutes and his time, 2:12:19.8, was a personal best time. Karel Lismont of Belgium was second in 2:14:31.8. Mamo Wolde, the defending Olympic Champion was third in 2:15:08.4. Kenny Moore was fourth and Bacheler ninth in 2:15:39.8 and 2:17:38.2, respectively. It was a great showing for the Americans.

As a running blog writer I have been in contact over the years but had never heard that story. I was also curious about the coaches who went into the Peace Corps on one year contracts and whether they worked under different conditions from the people going in for two years. The following is Roy’s response to my query. It also indicates his prolific writing talent.

While we referred to ourselves as members of a branch of the PC called the Sports Corps, we were indeed plain vanilla Peace Corps volunteers.

We went thru the typical language and cultural training, got a “salary” of 600 pesos a month = $100.

We were attached to the national governing body, lived mostly in a room in the old national stadium and existed on Red Stripe beer and lots of rice, eggs and chicken. Maybe some dog?

I got in great shape training the distance candidates and decided to try my first steeplechase at their national championships which were also their Olympic trials.

Came to the first water jump, slipped on the wet hurdle, went straight up in the air then down into the deepest water with only my bald head showing. Fans loved yelling “Calbo” (baldy) as I came past the grandstand. Even though I managed to pass several runners, I still finished last because they would drop out when I caught them.

Thru all these years I wrote monthly columns for Running Times and Racing South mags. “Heart Rate Training” by me and friend Declan Connelly has had 2 editions selling over 26,000 copies and translated into French, Italian, Czech and 3 versions of Chinese.

In a future article I will share a New York Times article about the early days of distance running in Tanzania written by one of my Peace Corps colleagues Stephen Fisher, but it would be too long to add to this particular posting. George Brose

Sunday, February 19, 2023

V 13 N. 22 Track Broadcasting 69 Years Ago

I recently was given the responsibility for caretaking a collection of old track and field files which will eventually be scanned and digitized so researchers, historians, and others can have access to these gems of the past. Most track nuts would give their last functioning testicle to have these in their home. Is this why we call them 'track nuts'? Some I will share on this blog. Today's piece is an editorial from the NYTimes concerning the broadcasting of the Miracle Mile at the Commonwealth and Empire Games of Vancouver, British Columbia in 1954. It was, as some of you may recall, possibly the first sporting event covered coast to coast live on the boob tube. I personally cannot remember if I watched it, but I did see the John Landy , Jim Bailey dual from the Los Angeles Coliseum two years later on May 5, 1956.

Anyway, the editorialist is less than happy about the way the race was broadcast. It was shot in Canada, but Canada did not have cross country transmission, so it had to be channeled to Seattle and then to Buffalo and back to Toronto and NYC for the director as you will see. I've transcribed the piece as it may be too difficult to read the photocopy.

Television in Review

N.B.C. Coverage of Empire Games Almost

Like Running 4-Minute Mile Backward

SOMETIMES television gets lost in its own electronic jungle. Last Saturday, N.B.C. went to great effort and expense to cover the British Empire Games direct from Vancouver, B.C. Then, in a bewildering state of confusion, it spent most of a one-hour program having TV emissaries tell the story second-hand from the R.C.A. Exhibition Hall in New York.

The main event in Vancouver was the eight-man "miracle mile" that pitted Roger Bannister (not yet knighted to Sir Roger, ed.) of England against John Landy of Australia, the only two men to break the four-minute mile. The running of the race was beautifully captured by the TV cameras, but the remainder of the program was disjointed beyond reason. It was marred by erratic switching between the R.C.A. Exhibition Hall and Vancouver and the frequent intrusion of ill-timed public service films.

Ben Grauer, head man of the hall, had a hectic afternoon trying to coordinate the segments and maintain telephone contact with Vancouver. The start of the race all but got lost in his frequent instructions for the camera crew there to be on the alert for the arrival of the Duke of Edinburgh. At one point Mr. Grauer, whose work evidently had not been too well laid out by N.B.C, grabbed the phone and asked: "Any word yet from Edinburgh? I mean Vancouver."

Mr. Grauer's studio guests included Wes Santee, the track star currently in the Marine Corps, Kenneth (Tug) Wilson and Asa Bushnell, president and secretary, respectively, of the United States Olympic committee, and Jesse Abramson, sports writer for the New York Herald Tribune. There would have been nothing wrong in having them on the show briefly to build up the race, but Empire Stadium, Vancouver, should have been the dominant part of the show, not a New York studio.

Probably the lengthiest single pickup from Vancouver was the race, a mere time of 3:58.8. The moment Bannister won the race and collapsed into the arms of some persons at the finish line. N.B.C. put on a filmed announcement (Commercial ad). Viewers who had just witnessed one of the truly great moments in sports history, were denied the added thrill of seeing stadium guards fighting to hold back the crowds attempting to run on the field. And they didn't see the dozens who hoisted Bannister to their shoulders and danced with him around the infield.

The race itself was ably described by an unidentified announcer, who it later turned out was a Canadian. But he never was allowed to summarize what he had seen or even to report the official time of the race. This commentary was reserved for Mr. Grauer and the experts 3,000 miles away in the R.C.A. Exhibition Hall.

The show also failed to dramatize interesting technical matters. Actually, it came about because the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation wanted to televise the race on its stations in Eastern Canada but had no relay facilities from the west. N.B.C. stepped in and had the signal fed from Vancouver to Seattle, which necessitated the construction of relay towers, and from there across the United States to Buffalo and then north to Toronto.

It certainly was a nice gesture by N.B.C., and it is hoped that Canadians saw more of their Empire Stadium than we did. V.A.

Today when I complain about modern track and field coverage, it seems as if some of these same issues come up. Maybe it is just endemic to the sport.

Now let me give you the link to the Canadian version of this story with two clips of the famous race in its entirety and some post race carrying on along with a clip of the tragic end of the marathon with Jim Peters collapsing before getting to the finish. Peters actually crossed what he thought was the finish, but the British team doctor misinformed him of the true location of the line. George Brose

British Empire Games 1954 Vancouver Link for fun count the number of times Landy looks back.

from Geoff Pietsch

" I watched it live. I remember that the papers said it was the first coast to coast such broadcast. And I remember rooting for Landy, the frontrunner. I also realized afterwards, when newspapers reported Jim Peters' collapse, that TV didn't show it even though it was a very short time after the mile. "

Saturday, February 18, 2023

V 13 N. 21 21st Century Track and Field Reunion Luncheon, Mount Sac Invite

Russ Reabold asked us to put this on the blog for any of you Southern California residents.

Mt. Sac Track and Field Luncheon Feb. 25, 2023 Details

Have a great time. Knowing that you are very likely to meet a few celebrities, I'd like to share the following discussion of what to say to someone famous if you have never met them.

It started when I saw the notice this week that major league baseball player and announcer Tim McCarver had passed away. It brought up this memory which I shared with a few people.

I was not next to Mr. McCarver like you, but saw him several times in main library, once when walking up steps to second or third floor right behind him and his girlfriend. She was a Pi Phi I think and my roommate Tom Raley dated, then married a Pi Phi so he may have known him better. Every baseball catcher possesses incredible athletic skills (i.e. how do they do that?), and in MLB, World Series, at highest level. Sheppard Miers

Friday, February 17, 2023

V 13 N. 20 A Wee Line or Two About An Arse Bedraggled

Image from website TherealXC.com

This piece was inspired by an invite to celebrate a Robert Burns night gathering a few weeks ago. Each invitee was required to bring a poem to celebrate the noble Bobby Burns. And so my humble doggerel below. The reader may want to self inform on the meaning of Athol Brose by the end of this. No worry, an explanation will follow.

Cold Sores on an Aging Rump

by George Brose

Composed for a Bobby Burns Gatherin’ February 4, 2023

The day was cold and full of rage when I hit the road on what seemed a tune up, a final phase .

Butterflies and grizzly bears slept in winter beds warm and dreaming of coming days.

But no, myself I had to prove what I already knew would be an agonizing test, my bum would freeze.

Off went the sweatshirt at the end of mile three,

And soon thereafter off came the tee.

By lap two I was peeling off the tights and feeling a warmth that promised I’d soon be to Elysian heights.

But, ‘twas not to be as I failed once more to spy that strip of hidden ice in shadow betrayed by beer-

glazed eyes.

Soon 'twas I a flyin' through the air not toward yon finish line but rather bleak despair

Yes, and so to land on matted hair.

Behold a scalp wound was all did wrought as I broke my fall with gluteus caught

In yon twisted wire fence,

The barbs of which were ne’r so dull as Michael Pence.

My arse was gouged by fiendish wire

And misfortune imbued by muck and mire.

My pager smashed by wanton fall and so for help I could not call.

Carried on by pride, the fool, soon to rue that decision, uncool,

Which came from bum rather than brain.

As time wore on my arse knew pain.

A breeding ground grown fetid with germs and maggots, worms and snot

Wracked by pain, relenting not

A twitch from the added strain

Of picking up the pace,

Headwind hard burnished my face.

With storm a brewing, knowing to stop was nothing doing.

Arrived to ER, butt bedraggled, that freaking fence was still entangled.

‘Tis a royal screwing near at hand.

But not of me, just my medical plan.

As multiple docs would each consign a consulting quack to check my spine

To recommend a test not yet invented

So when I’m billed, I’ll be indebted.

And so I rest these weary bones ‘neath bended willows scarfin' scones

Reading Burns and barfing Haggis

Jawing with runners, we’ll feed the maggots.

Think you that I am weak, well 'nigh morose ?

Not true, I know what means a dose,

Of intervals, fartleks, snowy roads (Sigh!)

Now but a laddie a stayin’ close

Who dreams of drinking Athol Brose*

*Athol Brose , a traditional Scottish drink made of wild honey, scotch, cream, and the elixir of water poured off soaking raw oats.

Athol Brose recipe from The Louisville Courier Journal, 1906

What an awesome Burns parody:

But if one were prone to believe the tale,

One would never approach the swale,

Hence one would never enjoy the thrill

Of simply running up a hill.

Will "Shakeschnier"

Thursday, February 16, 2023

V 13 N. 19 Lope Magazine and the 1955 NCAA XC Meet-Closest Finish Ever

This hobby keeps helping me come across new treasures that I never imagined were out there in the cyberworld. Last week I found another. It is called Lope Magazine. It was produced by a young runner named Liam Boylan-Pett. Liam was an outstanding runner at Columbia University and became an overnight sensation when he anchored his team to victory in the 4x800 relay at the Penn Relays.

I contacted Liam asking for permission to print his story about the 1955 NCAA cross country championship at East Lansing, MI which was won by Deacon Jones of Iowa over Henry Kennedy of Michigan State, still the closest finish in NCAA history. Jones was also the first African American to win the title. Liam Boylan-Pett is a very good writer and has an understanding of history to look back so far to tell us about this race.

For me the article stuck a bell I had long forgotten. Liam cites a 1956 issue of Sports Illustrated which had a number of color photos of the 1955 race. It was my first exposure to the world of cross country. They ran on snow covered ground that day, in shorts, and it did not look that inviting. In another year I would be doing that to help get in shape for the coming basketball season. Basketball ultimately didn't work out for me but cross country and track did.

Each year the issues of Lope Magazine were compiled into book form which can be seen on the website, however it seems to be in a hiatus as Liam has taken on a few more responsibilities like helping to raise his first child. I'm not sure you can even buy one of the books, but you can read all the issues on the website. So here is that story about the 1955 race, and at the bottom I will give you the link to that same story, and you can see the pictures of the race, as we cannot reproduce them without permission from Michigan State University.

By A Stride

by

Liam Boylan-Pett

from Issue 26 of Lope Magazine

* * *

On November 28, 1955, a 28-year-old John G. Zimmerman stood just off Hagadorn Road in East Lansing, Michigan, freezing his ass off. Zimmerman positioned himself with his camera at the edge of the forest on the northeast corner of Michigan State University of Agriculture and Applied Science’s campus. The surrounding trees buttressed at least some of 37 mile-per-hour wind gusts that made the 12-degree temperature bite even more. Zimmerman was there on assignment for Sports Illustrated.

The magazine was young; its first issue hit newsstands in 1954. Zimmerman had worked gigs for Time, LIFE, and Ebony. He always seemed to snap the shot, and his career took off because of it. In 1950 when he was working for Time, he was one of the first photographers on site when Puerto Rican nationalists attempted to assassinate President Harry Truman. By 1956, he was hired as one of Sports Illustrated’s first staff photographers, and became famous for his unique angles, groundbreaking lighting techniques, and use of remote-controlled cameras. He left to work as a commercial photographer in 1963, but remained one of the magazine’s favorite photographers, shooting over one hundred covers by his death in 2002.

On that frigid day in 1955 in East Lansing, however, he was still a young photographer on the verge of an iconic career. Hiding from the wind, Zimmerman was shooting the N.C.A.A. men’s cross-country championship race. He had positioned himself just before the 2-mile mark. His view was about 150 meters of a snow-covered path with towering, leafless trees lining both sides—pecks of dirt peeked up through the tire tracks of a vehicle that had traversed the course to make sure it was runnable earlier that day.

Looking down the trail, Zimmerman eventually saw a small orange dot bouncing on the horizon. It grew quickly: It was a winter hat perched atop a runner’s head. A pack of four had broken away from the pack. Michigan State sophomore Henry Kennedy—wearing a cap that would blend right in in a crowd in Brooklyn today—led New York University standout George King, who followed single-file behind him. University of Southern California’s Max Truex was about five yards behind and Connecticut University’s Lew Stiegletz was another five yards back.

As they neared, Zimmerman peered through the viewfinder on his camera like a birder stalking an endangered species. The crunching of their shoes grew louder as they inched closer and closer into the frame of his shot. Finally, just as Kennedy began a long, left turn that would loop him back towards the long push for the finish about 2 miles away, Zimmerman clicked the shutter. It opened for an instant, capturing the four runners in the front of the race and, about 70 yards back, the rest of a strung-out pack.

He stayed for a bit longer to snap a few more photos, but eventually, he traversed the college campus and its 4-mile cross-country loop along the Red Cedar River back to the finish line, about a mile-and-a-half away at the baseball fields on the northwest side of campus. There, he snapped more photos of runners in the finishing chute before leaving the scene and eventually developing the photos and sending the negatives along to the Sports Illustrated offices.

One year later, the photos were published alongside a story headlined, “Defiant Harriers.” The piece was short—a preview of the 1956 N.C.A.A. cross-country championship over a two-page spread. The headline was accompanied by a photo from the finishing chute, with runners from Kansas and Iowa cupping their glove-covered hands over their ears to stay warm. The caption read, “Nipping frost plagues runners in one of the most memorable N.C.A.A. cross countries ever held at East Lansing.”

The photo on the right side of the spread was the one from the forest off Hagadorn, of four runners leading a pack.

If one looked closely in the background, however, they could spot an unrecognizable pack of runners, blobs of blue and orange. One runner is nearly recognizable on the south side of the trail, dressed in yellow and black—the colors of Iowa University—and white long johns. He is at least 10 seconds back at the 2-mile mark, but he is important to the story of the race. Because over the next mile of the race, Iowa’s Charles “Deacon” Jones passed runner after runner until he found himself just behind Michigan State’s Kennedy with one mile to go.

Over the final 1760 yards of the 1955 N.C.A.A. cross-country championship, Iowa’s Deacon Jones and Kennedy would stage one of the best stretch duels the N.C.A.A. cross-country meet had ever seen, with one winning by just one-tenth of a second—or, as the Sports Illustrated story described it, “by a stride.”

It remains the closest finish in the meet’s history.

For all the great photos George Z. Zimmerman took throughout his career, it is safe to say he missed one in East Lansing that day.

(Sports Illustrated photo of Henry Kennedy, Lew Steiglitz, Max Truex) ed.

* * *

In the early days of N.C.A.A. men’s cross-country, East Lansing was the center of the universe. It hosted every N.C.A.A. Championship meet from 1938 (the first N.C.A.A. cross-country championship) to 1964. Michigan State University was Michigan State College back then (it would become Michigan State University of Agriculture and Applied Science in 1955 and officially dropped those last five words in 1964), and from 1939 to 1958, the Spartans won eight national championships and were runner-up twice. Coach Karl Schlademan had come to Michigan State in 1940 to coach the track and field team, but he also served as an assistant coach for the football team. Schlademan had done his best to learn from the cross-country coach, Lauren Brown, and took over in 1946. He was successful almost immediately: From 1948 to 1952, the team won three N.C.A.A. titles.

The next two years, however, Michigan State finished sixth and tenth at nationals. They needed to right the ship in 1955, the year of the school’s centennial. And a Scottish-born Canadian named Henry Kennedy, who went undefeated as a freshman (back when first-years did not compete on the varsity squad), was the right athlete to lead the way. According to Mark E. Havitz’s history of the Michigan State cross-country team, “One Hundred Ten Years Running on the Banks of the Red Cedar,” Kennedy worked mornings at the campus cafeteria making breakfast, later saying, “I was getting up at six to make breakfast; not for the people who were going to eat, but for the people who were going to make breakfast for the people were going to eat.”

The early work hours were not a problem for Kennedy, who ripped off wins in dual meets against Michigan, Notre Dame, Penn Sate, Wisconsin, and Ohio State to kick off the fall season. His winning margin was never less than 26 seconds. At the I.C.A.A.A.A. championships in Van Cortlandt Park, Kennedy ran away from the field on the 5-mile course, winning by a commanding 415 yards in a time of 24 minutes, 30.3 seconds. The team finished second to Pittsburgh, but still had the Big Ten meet and N.C.A.A.s to prove themselves.

Michigan State put up a dominant 36 points at the Big Ten meet in Chicago as Kennedy pushed a furious drive to home over the last half mile, pulling away from Iowa’s Deacon Jones to win by 15 seconds.

Kennedy was undefeated with only one meet remaining on the schedule: The N.C.A.A. Championship. Not only was Michigan State one of the favorites to win the team crown, Kennedy was a favorite for the individual title, a race no Michigan State athlete had ever won. And he could do it on his home course.

On November 28, 1955, Kennedy ignored his coach’s advice to wear long johns in the frigid, windy conditions. But when the gun went off at Old College Field that morning, Kennedy was not worried about long johns. Wearing an orange winter cap, a long sleeve shirt under a tee that was under his singlet, and gloves, he burst to the front of the race and took control like he had done in every race he ran that fall. According to the student-run Michigan State News, with a small lead pack, Kennedy ran by the first half-mile in 2 minutes, 18 seconds and came through the mile mark in 4 minutes, 45 seconds. It was the fastest mile he would run all day. Over the next mile, he led a group of four—the runners from N.Y.U., U.S.C., and Connecticut that would eventually be in the Sports Illustrated photo—through a 5 minute, 5 second mile, crossing the two-mile mark in 9 minutes, 50 seconds.

In the winding trail of what is now the Sanford Natural Area on Michigan State’s campus, Kennedy—though still slowing from his first and second miles—began opening a gap on the breakaway pack. “We entered the woods, which was my favorite place for moving out because of all the little sharp bends and rough underfoot terrain,” Kennedy later said in the oral history of Michigan State cross-country. “There were some very, very sharp turns on that part of the course. I always took three or four fast steps coming around the corner to pick up another two or three yards from the guy behind me.”

There was one problem with working that part of the course, however: The wind gusts were stronger than ever once Kennedy left the woods 2.5 miles into the course. He had dropped those in the pack with him—he also ditched his orange cap—but now there was no one to hide behind for respite. Kennedy would later call the strategy stupid. And by the 3-mile mark, which he crossed in 15 minutes, 3 seconds, there was another runner on his heels. Not one who had been in the pack of four, though. No, this was a runner from Iowa in a long sleeve and white, waffled long underwear who had run three consecutive miles right around 5 minutes flat.

With one mile to go, Deacon Jones was right on Kennedy’s shoulder.

“I was definitely a rarity in those days,” Deacon Jones told the Omaha World Herald in 2005. “I was a Black athlete from Nebraska who was a distance runner. People kind of did a double-take when they saw me out there.”

Jones grew up in St. Paul, Minnesota, but as a 13-year-old in a troubled family, he packed up and went to Boys Town School, just west of Omaha, Nebraska. Jones thrived there, especially once he got into sports. He made friends with some other Black kids in the Logan Fontenelle Projects of Omaha, including Bob Gibson, who would go on to become one of the best pitchers in Major League Baseball for the St. Louis Cardinals. At 5-foot-10-inches, Jones was a star on the Boys Town, football, basketball, and baseball teams, but he excelled most in cross-country and track.

In 1948, the year he moved to Boys Town, Jones entered a track meet because of the “race medal.” Third place got a scoop of ice cream, second got two, and first place was good enough for three scoops. Jones didn’t feel like the fastest kid in town, so he entered the mile. He only had a pair of street shoes, more like dress shoes than Converse All Stars. He won the mile in 4 minutes, 35 seconds. “I don’t know why everyone was so excited,” he would later say, “I was just running for ice cream.” Soon enough, he was running for more than that.

He would drop his mile best to 4 minutes, 17.8 seconds by his senior year to set the national high school record in the mile in 1954, and was recruited to Iowa to run on the track and cross-country teams. He quickly became a star in Iowa City, too. Having just finished his sophomore year, he qualified for the 1956 Melbourne Olympics in the 3,000-meter steeplechase, and placed ninth. By the time he graduated from Iowa, he was the American Record holder in the steeple and one of the most decorated athletes in Iowa history.

At the 1959 Pan-American Games in Chicago, Jones, who had learned to cut hair in his time at Boys Town, was in a dormitory with some of his other track and field teammates on the U.S. team. The boxing team was in the same dorm, and one afternoon with a bunch of track guys hanging out, Cassius Clay walked in, asking for a haircut. He wasn’t the world-famous boxer yet, but he was still the man who would become The Greatest, and he didn’t love the flat-top Jones had given him, talking trash and telling Jones to be better. “If you want a better haircut,” Jones shot back, “you have to come in here with better hair.” The room erupted in laughter.

Jones also met Lou Brock in Chicago that summer. Brock, who died this September, was also a star for the St. Louis Cardinals, and set a then Major League Record of 938 stolen bases when he retired in 1979. It turned out, Jones had offered him some advice on improving speed. Those tips kept coming over the next 20 years as Brock became a star.

At the 1959 Pan American Games, Jones won silver in the steeplechase.

Jones made the 1960 Olympic Team, too, taking seventh place in the steeplechase in Rome.

Jones was not just a steeplechaser, though. He was pretty good at cross-country, too.

And one of his best races over hill and dale came in East Lansing on November 28, 1955, as a sophomore at Iowa. It was bitterly cold. Jones was one of the few runners to wear long johns under his team-issued white shorts. He only wore a white T-shirt under his yellow Iowa singlet. His ankle-length socks kept his toes warm in his Adidas spikes that had been taped at the arch of his feet to keep them cinched tight over the frozen ground.

When the gun went off, Jones ran under control. Just weeks earlier, Kennedy had used a long push from 880 yards out to drop Jones, who had tried to stay on his shoulder for as long as possible. In East Lansing, however, Jones let Kennedy go. While Kennedy came through the first mile in 4 minutes, 45 seconds in a pack, Jones was biding his time about 10 seconds back. The gap remained similar over the next mile, with Jones coming through 2 miles right at 10 minutes. He, like Kennedy, used the woods to stake his claim on the race. Over the next 5 minutes, Jones closed the gap to Kennedy. Hitting the headwinds when he exited the forest, Jones reeled in Stieglitz, Truex, and King one by one.

With one mile to go, he was on Kennedy’s shoulder—and he was ready to kick, too.

Scattered in half-mile increments along the Michigan State cross-country course that day were Cadet Officer Corps members of Michigan State’s R.O.T.C. Each had a radio. As runners passed, they would relay information back to the P.A. announcer in the bleachers near Old College Field, where the race started and ended.

Throughout the first three miles of the race, the spotters or the P.A. announcer confused Michigan State’s Kennedy for his teammate, Selwyn Jones. The announcer informed the crowd and media in East Lansing that it was Jones, not Kennedy, leading the race at the mile and the 2-mile. (Thanks to Zimmerman’s Sports Illustrated photo, we know that was not true.) So, it might have come as a surprise when a cadet reported two runners fighting for the lead at the 3-mile mark were Kennedy and Jones.

Running along the Red Cedar River, the two crossed in 15 minutes, 3 seconds. The race was on.

Kennedy, like he had done at the Big Ten meet, pushed from far out. His splits had gotten slower with each passing mile, but he somehow picked up the pace over the final five minutes of the race. He had not lost a race all year. He had beaten Jones the last time they faced off. Kennedy was sure he was going to do it again. But as he drove harder and harder for the finish, Jones stayed on his shoulder, waiting to strike. The two sophomores looped around a snow-covered golf green on Old College Field, and then, with less than a quarter-mile to go, Jones made his move.

“He jumped me with 300 yards to go,” Kennedy would later say. It was a burst of speed, but it did not break the Michigan State star. The course straightened out, and Jones was a foot or two in front. Jones pushed the gas, increasing his cadence, kicking up bits of snow and blades of frozen grass. Kennedy stayed on him but could not gain an inch. Kennedy searched for any bit of energy in his reserves, but there was nothing there. Jones, meanwhile, had taken his shot. It had worked, but he had to hold on. Over the last 100 yards, he stayed just in front of Kennedy.

After the Big Ten loss, Jones had told his coach he thought he could beat him next time. He simply needed to time his kick correctly. As he held his lead over the race’s final moments, the prediction proved true.

Jones surprised Kennedy with 300 yards to race. The two then battled over the next 45 seconds, urging their bodies to go just one tick faster. Neither gave an inch. In the end, Jones held off Kennedy to win by one-tenth of a second. They closed the final mile in 4 minutes, 54 seconds to run 19 minutes, 57 seconds for 4 miles—Jones was officially timed in 19 minutes, 57.4 seconds.

It was the closest finish in N.C.A.A. history. It was the first time a sophomore had won the race. It was the first time an Iowa Hawkeye had won an individual title. And it was the first time a Black athlete had won the individual crown.

In 2018, Wisconsin’s Morgan McDonald held off Stanford’s Grant Fisher in the final straight of the 10-kilometer race in Madison to win by five-tenths of a second. The year before, Syracuse’s Justyn Knight beat Northern Arizona’s Matthew Baxter by seven-tenths. Both races were tight, but Jones’ victory over Kennedy remains the closest finish in N.C.A.A. history.

The N.C.A.A. cross-country season is going to be different this year. Because of the coronavirus pandemic, the N.C.A.A. approved delaying the season until the spring of 2021. The wait for another great homestretch duel will have to wait until March.

Michigan State did win the team competition in 1955, scoring 46 points to Kansas’ 68. It began a string of dominance. The team won in ’56, ’58, and ’59 and was runner up in ’57 and ’60.

Henry Kennedy graduated from Michigan State in 1958, and went on to become a professor at the University of Central Florida. Kennedy’s brother, Crawford “Forddy” Kennedy won the individual N.C.A.A. cross-country in 1958. Henry is now retired and living in Titusville, Florida, outside of Orlando.

Charles “Deacon” Jones remains Iowa’s only cross-country national champion. The “Black athlete who was a distance runner from Nebraska” went on to a career for the ages—he was a pioneer in U.S. track and field. After his running career, Jones eventually settled in Chicago. He stayed close with Brock, and served as the financial aid director for the City Colleges of Chicago. He died in 2007.

There is another picture from that day in East Lansing. It was not taken by John G. Zimmerman. Today it is housed in the Michigan State University Archives and Historical Collections. The photo shows Henry Kennedy and Charles “Deacon” Jones. Jones’ arm is draped over Kennedy’s shoulder. Kennedy is patting Jones’ back. They both are wearily holding onto their sweat suits. Their hair stands up and back, windswept. They both look tired—Kennedy has a slight smile, Jones’ face seems to be saying, “Thank goodness that is done.”

If one did not know the results, it would be hard to say who won the race.

There is one more photo in the M.S.U. Archives that proves who prevailed, though. The photographer’s name has been lost in time, but he or she caught the photo of the day: Jones just an instant from the finish line, a stride in front of Kennedy in the closest finish in N.C.A.A. history.

At this point the photo of the finish of the race between Henry Kennedy and Deacon Jones can be seen on the website. ed.

Link to this story with the photos Be aware that your computer may slow down a bit while scrolling through the site. Mine does, but it gets over it. George Brose

V 15 N. 10 Gunder 'The Wunder' Haegg Visits Cincinnati

Bob Roncker of Cincinnati, Ohio has sent in this account of one day on the 1943 tour that Gunder Haegg of Sweden made to the US to help rais...

-

Bob Roncker of Cincinnati, Ohio has sent in this account of one day on the 1943 tour that Gunder Haegg of Sweden made to the US to help rais...

-

This posting was inspired by the piece we did a few months ago on the members of the 1960 Olympic track and field team who had passed away....