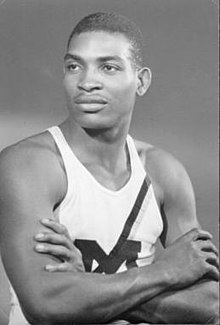

Charlie Fonville

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Charlie Fonville

| |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | Charles Edward Fonville |

| Nationality | American |

| Born | April 27, 1927 Birmingham, Alabama |

| Died | July 13, 1994 (aged 67) Detroit, Michigan |

| Occupation | Athlete, Attorney |

Charles Edward "Charlie" Fonville (April 27, 1927 – July 13, 1994) was an American track and field athlete who set a world record in the shot put. In 1945, he had been named the Michigan High School Track & Field Athlete of the Year. He won the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) shot put championship in 1947 and 1948. Competing for the University of Michigan at the Kansas Relays in April 1948, Fonville broke a 14-year-old world record, throwing the shot a foot further than the record.

Fonville was considered the favorite for the 1948 Olympic gold medal but a back injury prevented him from qualifying for the Games. After undergoing back surgery in November 1948, Fonville sat out the 1949 season, but came back in 1950 to win his third Big Ten Conference shot put championship. Fonville later became a lawyer and practiced law in Detroit, Michigan for 40 years. He was inducted into the University of Michigan Athletic Hall of Honor in 1979, as part of the second class of inductees.

Early years[edit]

Born in Birmingham, Alabama, he moved with his family to Decatur, Illinois at age 11. Prior to his senior year in high school, his family moved to Detroit. In 1945, following Fonville's lone track season at Detroit's Miller High School, he was named Michigan High School Track & Field Athlete of the Year for his first-place performance at the Detroit City League Meet. Fonville's winning effort in the shot put was five feet better than that of the state champion. Later that summer, Charlie Fonville and Jessie Nimmons competed in the Detroit YMCA Track Championship as a two-man team for the St. Antoine YMCA; Fonville won the 100m, 200m, high jump, and shot put. Fonville and Nimmons won the 440 yard relay, with each of them running 220 yard legs. They were later disqualified for not having four runners. They finished in second place at the meet; their disqualification in the 440 preventing them from winning.

In 1945, Fonville enrolled at the University of Michigan without a scholarship and paid his way through college with summer jobs and working in a sorority dining room.

Big Ten shot put record in 1947

Fonville won the 1947 Big Ten indoor shot put championship. Early in the subsequent 1947 outdoor track season, Fonville was throwing over 53 feet (16 m) and was poised to break William Watson's Big Ten Conference record. At a meet in early May 1947, he broke Watson's Ferry Field record with a throw of 53 feet 10.5 inches (16.421 m). At the Big Ten outdoor track and field meet in late May 1947 in Evanston, Illinois, Fonville broke the Big Ten shot put record in the qualifying rounds. Henry J. McCormick, of the Wisconsin State Journal, reported that "Friday's finals were highlighted by the shot put, where Charlie Fonville set a new conference record of 53 feet 11.75 inches (16.4529 m), smashing the former mark of 52 feet 11.5 inches (16.142 m) which Bill Watson of Michigan set in 1938." Fonville then topped his own mark in the finals of the same meet with a throw of 54 feet 1 inch (16.48 m). The following month, Fonville continued to improve with a throw of 54 feet 10.875 inches (16.73543 m) to win the NCAA meet.

World record in 1948

Fonville won the Big Ten indoor shot put championship again in 1948. In April 1948, Fonville broke the world record in the shot put at the Kansas Relays with a throw of 58 feet 0.375 inches (17.68793 m). The previous mark of 57 feet 1 inch (17.40 m), set by Jack Torrance, had stood since 1934. The United Press reported:

Ironically, Fonville had felt he was not ready for the Kansas Relays. A back injury had discouraged him, and there was even discussion that he might not make the trip.

Fonville noted at the time that, in his opinion, speed was more essential than beef and weight in the shot put. Speaking about his technique, Fonville said, "You concentrate—and then you just try to explode across the circle." His coach, Ken Doherty, described Fonville as "one of the hardest working, most studious athletes" he had ever coached. Doherty also added that Fonville's technique distinguished him from most shot putters: "Fonville drives completely across the ring in one continuous motion. Previously, most shotputters made their initial hop and hesitated before their final drive. ... Any track coach looking at him, would recognize all the points of good form. The only difference is that he has unusual speed and quickness—and he is the greatest competitor I've ever coached."[9] One columnist described Fonville's steady improvement from his freshman year in 1946 through his junior year in 1948 and concluded: "Small as shot-putters go, Fonville is the greatest in the long history of sensational 16-pound (7.3 kg) heavers."

Fonville's son, Carl Eric Fonville, later wrote that his father was troubled by the unequal treatment given to African-American athletes during the Kansas meet at which he set the world record. Upon arriving at the Kansas Relays, Fonville and Harrison Dillard of Baldwin-Wallace College were housed at the home of a black family.[1] His son wrote: "Without unpacking they decided to take a walk to the University of Kansas campus where they found the other visiting white athletes being given campus tours and their treatment far different than their own. They both considered leaving but decided to stay and compete. Charles called Ann Arbor, Michigan to tell them that he wanted leave, he got Don Canham who told him that he was 'Sent to Kansas City to represent the University of Michigan,' the conversation was short and clear."[1] Fonville and Dillard both set new world records at the event.

In June 1948, Fonville successfully defended his NCAA championship at the NCAA meet in Minneapolis, with a throw of 54 feet 7 inches (16.64 m).

Back injury and Olympic disappointment

Even before the Kansas Relays, one writer stated: "Michigan's Charley Fonville has only to retain his present form to be a certain Olympic games winner in the shot put." After a record-setting performance at the Purdue Relays, the United Press noted that "American Olympic stock was several points higher today." And after he set the world record at the Kansas Relays, the United Press reported: "You can write down the names of the midwest's terrific trio—Harrison Dillard, Fortune Gordien, and Charley Fonville—today as sure leaders of the U.S. Olympic track and field squad this summer. Out of the helter-skelter of three relay carnivals, ... these three emerged as Uncle Sam's surest hopes for glory in London."

However, Fonville had been competing with an ailing back all year. The injury worsened as the track season wore on, and in early July 1948, Fonville was forced to pull out of the National AAU track and field championships due to a "strained back." Michigan's coach, J. Kenneth Doherty, informed the meet of the injury but "did not say how severe the injury was nor if it would keep Fonville from Olympic competition."

Fonville competed in the Olympic trials in Evanston, Illinois in mid-July 1948, but he was not able to meet his own standards as a result of the injury. He finished fourth and, despite having broken the world record just three months earlier, did not qualify for the U.S. Olympic team. There were some who suggested that Fonville should be named to the Olympic team despite his fourth-place finish at the trials; others argued it would be unfair to the third-place finisher to take away his spot on the team. And "there was also a suspicion that Fonville's ailing back hadn't healed and that his performance at Evanston represented the best he can do at this time."

"The competition in these trials is merciless, but it's fair. ... Still there was heart-break aplenty at Evanston. There was Fonville, the rangy University of Michigan Negro who broke the Olympic shot put standard by almost a foot and still couldn't win one of the top three places. Fonville had tossed the shot repeatedly for distances that would have earned him a berth, but—to quote his own words—'I just didn't throw it far enough this time.'"

Wilbur Thompson won the gold medal in the 1948 Summer Olympics with a throw of 56 feet 2 inches (17.12 m)—almost 2.0 feet (0.61 m) shorter than Fonville's world-record distance.

Despite not making the Olympic team, he remained Michigan's most valuable track and field star, and at the end of the 1948 season he was chosen by teammates as captain for the 1949 season. However, in the fall of 1948, the severity of Fonville's injury was discovered, and it appeared he would never compete again. In October 1948, after observing Fonville for a month, specialists at the University of Michigan Hospital concluded that Fonville was suffering from a fused vertebrae. He apparently had the ailment since birth, but had aggravated the condition throwing a 16-pound (7.3 kg) iron ball in event after event. The Associated Press (AP) reported that the injury "has ended the Michigan star's brilliant collegiate shot-putting career."

In early November, doctors operated on Fonville, placing a bone graft onto his cracked vertebrae. After the surgery, doctors described the procedure as "100 percent successful." Fonville refused to give up, saying at the time of the operation that, though he would not compete in 1949, he had been troubled by his back for two years and hoped the operation would cure him and allow him to compete again in 1950.

Comeback in 1950

After sitting out the 1949 season to allow time for his back to heal from the surgery, Fonville returned to competition in 1950. The 1950 U-M yearbook, Michiganensian, simultaneously lamented about and praised Fonville's comeback, noting his return to form with a 55 feet 1 inch (16.79 m) throw in the Michigan A.A.U. meet in January and describing how it would have earned second place in the 1948 Olympics. However, Fonville was not able to throw at the distances he reached in 1948. After a victory in a meet against Wisconsin, The Wisconsin State Journal said: "Charlie Fonville, the former world recordholder in the shot put, heaved a creditable 53 feet 7.5 inches (16.345 m) to win the event. The Negro star, sidelined for 18 months, returned to competition three weeks ago to heave more than 55 feet." He also won the Big Ten Conference indoor title for the third time. However, the AP noted that Fonville "returned to competition this season after laying out last year and either has lost his terrific snap or is favoring the back." Jim Fuchs of Yale broke Fonville's world record, and the AP reported: "An injured back, perhaps, is all that stands in the way of boosting the world's record for the shot put to 60 feet. Michigan's Charlie Fonville, the athlete with the bad back, was the world's best shot putter two years ago and still holds the official mark of 58 feet 0.375 inches (17.68793 m)." Though Fonville won the 1950 Drake relays, his winning throw of 52 feet 1.5 inches (15.888 m) was described as "comparatively puny" compared to the 58 feet 5.5 inches (17.818 m) throws of Jim Fuchs that year. In 1952, Michigan track coach (and future athletic director) Don Canham dedicated his book Field Techniques Illustrated to Fonville as follows: "Dedicated to Charlie Fonville a world record holder who accepted disappointment as graciously as he did fame and success."

Later years

After graduating from Michigan in 1950, Fonville worked in labor relations at Kaiser-Frazer, an automobile manufacturer, while attending Wayne State University Law School at night. Fonville was a lawyer in private practice in Detroit from 1954 to 1994. In 1979, Fonville was inducted into the University of Michigan Athletic Hall of Honor. He was part of only the second class inducted into the U-M Hall of Honor, being inducted in the same year as Michigan legends Fielding H. Yost, Fritz Crisler and Willie Heston. The only U-M track athlete inducted into the Hall of Honor before Fonville was Bob Ufer. In 1994, Fonville died at the University of Michigan Hospital—the same hospital where he had surgery in 1948 to repair his vertebrae. He was 67 years old when he died.